This article is from the February 1982 issue of Dollars and Sense, available at http://www.dollarsandsense.org

This article is from the February 1982 issue of Dollars & Sense magazine.

40th Anniversary Highlight

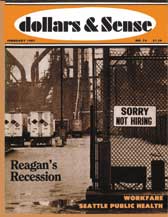

The Roller Coaster Heads Down

Ask yourselves, Ronald Reagan asked the electorate in 1980, whether you are better off or worse off than you were in 1976. Jimmy Carter could do little more than respond with a smile—remember that smile?—and recite platitudes about the need for sacrifice to reestablish a stable, healthy economy.

A year later it is Ronald Reagan who is issuing the smiles and the platitudes. The statistics portray a bleak picture for the first year of the Reagan presidency:

- The unemployment rate for December 1981 was 8.9% and rising, as compared to the already high 7.5% at the time of Reagan’s election. That’s an increase of some 1.5 million in the number of people looking for jobs. (See last month’s D&S for an explanation of what the unemployment figures really mean.)

- After an adjustment for inflation, retail sales—what people spend for food, clothing, gas, etc.—were 4% lower in November 1981 than in November 1980.

- Real take-home pay for the “average workers with three dependents” has fallen by 3% over the last year.

- And even business felt the pinch, as profits after taxes (and adjusted for inflation) were 11% lower in the third quarter of 1981 than in the third quarter of 1980.

Who Reads Yesterday’s Papers?

Reagan told the people who elected him that sacrifice would not be necessary. He promised a quick and painless solution to the problems of the American economy, one that would not require a recession as the price of reducing inflation. The campaigning Reagan claimed that tax cuts and budget cuts would stimulate economic expansion and provide more jobs, while increasing the supply of goods and services enough to avoid inflation.

But just as Ponce de Leon failed to find the fountain of youth, so did Ronald Reagan fail to find the magic cure for the woes of the U.S. economy. Instead, the administration has found itself faced with the same trade-off between inflation and unemployment that bewildered Nixon, Ford, and Carter.

Reagan made his choice, following an economic policy which has driven the country deep into a recession. He has even gone several steps farther than his recent predecessors by heavily cutting social programs and government employment, and by accepting a severe enough recession that labor feels forced to make wage concessions.

The Reagan administration has claimed that this pain is only temporary, that the good times will arrive soon, “toward the spring and going into summer.” But, what are the chances for “the magic cure” working sometime in 1982? Are the Reagan policies really leading toward “robust” expansion and a continuing decline in inflation? Probably not, and a look at some of the economic consequences of Reaganomics will explain why.

Deficits and More Deficits

Reagan the candidate vowed to balance the federal budget by 1984. The latest estimates from both the administration and the Democrat-controlled Congressional Budget Office, however, show the emptiness of this promise. Unless some unexpected changes occur in the economy or in the budget, the federal deficit will be about $100 billion in the current fiscal year, and climb even further to about $150 billion in 1984. Such deficits are unprecedented in sheer size, and they will be a greater proportion of GNP than any deficit since World War II (see graph in “Economy in Numbers,” page 10).

The deficit is large and growing because Reagan has combined extensive tax cuts with an increase in military spending. The administration sees both as essential components of its program to “revitalize” America. Yet, lower taxes means less money coming in, and more military spending means more money going out; the combined result is more deficit. Neither the real and very deep cuts in social spending nor the fantasy of rapid economic growth (which was supposed to yield more tax revenue even at the lower tax rates) can come close to filling the gap.

At the same time, the Federal Reserve System, which administers monetary policy in the U.S., is pursuing a course of “tight” money. This means that the Federal Reserve, with the tacit support of the White House, is restricting the availability of credit by slowing the rate of growth of the money supply. This policy is based on the belief that inflation is caused by excessive expansion of the money supply, and that if the Federal Reserve tightens up, inflation can be contained.

The Accelerator vs. the Brakes

The problem is that running the economy with the combination of large federal deficits and tight monetary policy is like driving a car with one foot on the accelerator and one foot on the brakes. The car may move forward slowly for a while, but it’s hard to predict what will happen after that.

On the one hand, in certain circumstances government deficits can have a positive effect on growth. If the economy is so depressed that business is not investing and consumer spending is way down, then deficit spending by the government can create jobs, and serve as the basis for at least a temporary recovery.

However, the impact of a federal deficit on production, employment, and prices is greatly affected by the monetary policy which accompanies it. A government which runs a deficit must borrow to finance the excess of spending over taxes, and a large deficit requires a lot of borrowing. In the past, the Federal Reserve has not maintained a tight money policy in the face of persistent deficits, because it feared that tight money would stifle growth and precipitate a financial crisis; instead, it would supply enough credit to accommodate the government’s borrowing demands at relatively low interest rates.

This time around, though, the Federal Reserve is acting tough in an effort to choke off inflation, holding down credit even when interest rates top 20%. With a limited amount of credit available, the government can outbid private borrowers for scarce funds, causing interest rates to rise. High interest rates, of course, lead businesses to postpone investments and consumers to delay purchases. This is hardly a prescription for economic recovery.

Excuses, Excuses

The latest consensus of the professional economic forecasters seems to be that recovery form this round of recession is unlikely even to commence before mid-spring. Consumer spending is weak, as witness the figures on retail sales mentioned above. High interest rates are preventing a recovery in the crucial housing and auto industries. Businesses are holding off on investment until they see some signs of growing demand.

The Reagan people have put the blame for this failure on previous administrations. They claim that almost every administration since the 1920’s had made such a mess of things that there was no way to patch up the economy quickly. Government mismanagement of the economy had so weakened business confidence that it could not be restored overnight; inflationary expectations were so strong that one round of budget cutting was not sufficient to wipe them out. So, Reagan asserted, we should view the current recession as the legacy of past administrations and not as his responsibility. The problems of the U.S. economy, though, were no secret to anyone who stayed awake through the 1970’s. So, while pointing to past errors is a favorite sport of every president, Reagan cannot excuse his lack of success by claiming that he didn’t know what he was getting into.

The Reagan administration has also latched onto any event that could possibly suggest that its economic policy is working. The major piece of evidence is the recent drop in the rate of inflation. Consumer prices were rising at an annual rate of about 6% by the end of 1981, as compared to their double digit rates through both 1979 and 1980. However, much of the decline can be attributed to the aftereffects of the Carter recession of 1980, to the recent glut on the international oil market, and to comparatively stable food prices. None of these events are due to Reagan; none of them will probably have much long-term effect on the underlying rate of inflation.

But government officials still maintain that the second half of 1982 will bring strong growth without inflation. Supporters of the Reagan policies proclaim that the tax reductions and the positive business climate created by their budget cuts will yield an “explosion” in investment. No government functionaries or supply-side gurus are able, however, to supply any evidence that tax incentives and a nice atmosphere can counteract high interest rates and the continuing outlook for slow, unstable growth. There are many industries operating with considerable excess capacity; a few tax breaks will not induce them to make any substantial investment, let alone create an “explosion.”

Of course, the Federal Reserve could change its policies, ease up and supply more credit. Since there is excess capacity and unemployed workers now, such a change might result in rapid economic growth in the short run, as the combination of easy credit and a big deficit would encourage business and consumer spending. However, and explosion in prices would undoubtedly follow close behind, leading to a great resurgence of inflation. The pattern would probably be similar to the one which has characterized the recession-recovery cycle in the past; each recession cuts the rate of inflation temporarily, but by the start of the next recession inflation has risen to new heights.

The Reagan Revolution

Thus, although the Reagan administration has drastically changed the economic role of government, it has not escaped the cycle of recession and inflation. One lesson worth drawing from this historical continuity is that the government cannot directly and precisely control the course of the economy. Yet while we are still on the economic roller coaster with Reagan, the ride with him is not quite the same as in the past.

By encouraging the current recession in the wake of the 1980 recession, the Reagan people have succeeded in placing the labor movement in a desperate position. Unions are being faced with the threat that strong demands may force their employers out of business. In the automobile industry, the United Auto Workers (UAW) is under pressure to make large concessions to the companies or see further loss of jobs. The Teamsters are also likely to make concessions when the Master Freight Agreement, covering 300,000 truck drivers and warehouse workers, is renegotiated in March. These responses by leading unions will probably set precedents for others. In the short run, unions will have a difficult time dealing effectively with the situation.

Moreover, the real Reagan “revolution” has taken place in social programs and government employment. During past recessions, social spending has provided some cushion for people out of jobs and government employment has continued to grow, countering the pressures created by unemployment in the private sector. Now, however, the sacking of government workers is making a major contribution to the rising unemployment figures.

Consequently, whatever else the current recession accomplishes, it is weakening labor and setting the stage for a shift of income toward business and the rich if and when recovery comes. However, while in the short run business may benefit, it seems unlikely that stable growth can be achieved by Reagan’s policies. In fact, in the current economic situation, it is hard to imagine much economic growth n this country without marked recovery in the auto and housing industries; and these are industries which depend directly on good incomes for the majority of consumers rather than on tax breaks for the rich.

More important than economic analysis, though, is the question of what most people—people who do not share in corporate profits or tax loopholes—will put up with. They are likely to ask themselves, as Ronald Reagan suggested they should, whether they are better or worse off than before.

Did you find this article useful? Please consider supporting our work by donating or subscribing.