How Yale Workers Defied Union Busting

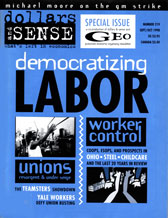

This article is from the September/October 1998 issue of Dollars and Sense: The Magazine of Economic Justice available at http://www.dollarsandsense.org

This article is from the September/October 1998 issue of Dollars & Sense magazine.

On December 17, 1996, a year-long struggle to preserve close to six hundred union jobs in the city of New Haven ended victoriously for Yale University workers. The workers were members of Yale's two union locals, both part of the Hotel and Restaurant Employees (H.E.R.E.)—Local 34, representing the predominantly female clerical and technical workers, and Local 35, representing service and maintenance workers.

The unions defeated the Yale Corporation after two bitter consecutive strikes, in which Yale hired union-busting consultants and tried to starve the workers out. This was only the latest chapter in many years of labor struggle at Yale, a supposed bastion of enlightened thinking.

The university had attacked Local 35 regularly during the 1970s. Local 35 realized that in order to survive they needed more unionized workers on campus, so they provided strong backing for Local 34's organizing drive in the early 1980s. Local 34 first won a contract in 1985, after a ten-week strike, and in the following years both unions were able to obtain good contracts through joint negotiations.

But in 1996 Yale renewed its assault on the unions, announcing plans to transform many union jobs into low-wage, contingent jobs and threatening to cut off the workers' health insurance if they went out on strike.

In 1982 Andrea Cole was a secretary in Yale's mostly anti-union Economics Department, and became a leader in the organizing drive for Local 34. After the 1984 strike, she was one of six rank and file organizers elected to full-time staff positions, and continued in that role during the 1996 strike.

The following article is based on a talk that Cole gave to union activists at a "Solidarity School" in September 1997. She spoke about the early days in the development of Local 34 and of the most recent victorious strikes.

—Marc Breslow

Yale is not simply an academic institution. It is run by some of the most influential corporate leaders of the world. In 1996, the Yale Corporation was prepared to pull out all the stops to crush us. In the end, the effort failed and the two unions shared a victory with the entire community. Yale, once again, had underestimated the resolve in our hearts and the depth of solidarity between the two unions.

All of us at Yale are still flushed with victory. It was an 18-month struggle that we waged against a very powerful institution that had clearly decided to break the unions. The university took advantage of the anti-union climate and of the current so-called "business trend" to hire more and more temporary workers with low wages and no health care benefits. The economy in Connecticut—and in New Haven, in particular—was bad. Given the climate and the corporate arrogance of the institution, it was natural for the administration to think that we would simply buckle under pressure. Yale started off by attempting to take back health insurance for people who were retiring. Then they tried to take 600 union jobs in the seventh poorest city in the nation, New Haven, and transform them into low-wage, no-benefit jobs—through contracting-out the jobs to a non-union employer. And as we were approaching our strike deadline they said they were going to cut off our health benefits if we went on strike.

To counter Yale's threats and to create an extended period of intense disruption on the campus, we implemented a "rolling strike"—first Local 34 went out for a four-week period, while Local 35 members contributed $100 each per week to a strike fund but did not observe picket lines. Then, when students left town for two weeks of vacation, everyone went back to work. When classes resumed, Local 35 went on strike while Local 34 members were at work and contributing $100 per week to sustain Local 35 strikers.

During those ten weeks Yale upped the ante even more by bringing in PLE—a security firm from West Virginia known for its provocative actions during strikes—in an unsuccessful attempt to provoke incidents of violence on the picket lines. When the two strikes were over, Yale stopped collecting all dues from both unions in an effort to cripple us financially. They spent huge amounts of money—literally millions of dollars—on a public relations campaign, which littered the community with letters and full-page anti-union ads. The attack was systematic and well orchestrated.

During all of this, however, we kept our focus on strengthening our organizing committee in each department on the campus. So, as each thing hit we had a committee ready to encourage our members in each work unit to stay strong. Through the organizing committees we were able to get information out quickly and effectively. It's hard to imagine how we could have won had we not focused our efforts on working with the organizing committee. It was, and still is, the absolute backbone of the organization.

We measure our strength by how many people we have who are tied into the committee structure and on how bold that committee is prepared to be. If, for example, an organizing committee member is simply prepared to take an informational leaflet and hand it out to the person next to her or him—and is too nervous to have a conversation with the person—we have a weak union.

We have a much stronger union if a committee member is prepared to engage in a struggle with a co-worker. If, for example, she can say to a worker who may be in severe debt, or who may have a sick child or husband, "Look, we have to do this together—we have to get up and walk off this job and stay on the line for as long as it takes," then we have a strong union. Or, if the committee member is prepared to go with her to confront her boss directly about the boss's unfairness, and to bring along the other workers in the department, then we have a strong union. Fundamentally, it was our willingness to challenge one another's fears on the job that led to our ultimate victory. But equally important, it was our willingness to reach out to our communities.

Not long into this most recent fight, it became evident that the 600 jobs at risk did not concern us alone. Even though the university littered the campus and the city with misinformation, we had our organizing committee to rely on. Members of the organizing committees in the departments now became active in their own neighborhoods. We said, okay, in that neighborhood we have these eight people who are on the organizing committee in various departments. They may be in different departments, but they are all leaders of the union. Let's now have neighborhood organizing committees that will organize neighborhood meetings. We will take our message to members of the clergy, our elected officials, our neighbors, and our families. We'll tell them what the real story is here—what's really happening at Yale and what the impact of Yale's plan will be on our communities.

We identified exactly where our committee members lived in each one of the New Haven neighborhoods and in the small neighboring towns, and we formed neighborhood committees right where they lived. Over a two or three week period we held 13 neighborhood meetings which were attended by a total of about 2,500 people.

That was a very empowering experience, and it started to turn the tide. We started to sense it, to feel public opinion shifting toward us, and to feel confidence that the victory was coming. Community leaders, members of the clergy, and elected officials started to really understand what was happening. They started to feel that what the university was doing was unjustifiable. In the wake of the commmunity meetings, the Greater New Haven Clergy Association drafted a bold statement that portrayed the university administration as Goliath, using the full force of its economic power against two little "David" unions. One hundred and five clergy members signed the statement, which was then published as a full-page ad in the local newspaper. The publication of the statement had a powerful effect on the community. People now wanted to stand with us. It had become a common struggle.

On December 10, 1996—very shortly after the 'David and Goliath' statement was published—three hundred and twelve people participated in a civil disobedience action in the heart of the Yale campus. Union members stood side by side with members of the clergy, leaders of civil rights organizations, and elected officials in the arrest. Seven days later, a settlement was reached. It was a victory shared by an entire community.

This was a long and bitter struggle, but we came out of it with the 600 jobs that Yale wanted to contract out still intact, good raises, and no increases in the cost of health insurance for either workers or retirees. Incidentally, in the middle of it all we actually held a union election for contingent workers the university was using as part-time laborers, and under the terms of the new contract, many temporary employees are now in the union.

But our work is far from done, even though both unions came out with good contracts. We, as working people, must continue to develop leadership within our own ranks. We must see that it is possible to win. And we must be ready to challenge ourselves. Shame on us if we are not willing to give others the opportunity to be bold and to step out there in defiance of any employer that attempts to rob us of our dignity, our respect, and fair compensation for an honest day's work.