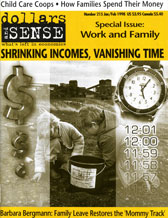

Watch Out For Family Friendly Policies

This article is from the January/February 1998 issue of Dollars and Sense: The Magazine of Economic Justice available at http://www.dollarsandsense.org

This article is from the January/February 1998 issue of Dollars & Sense magazine.

What could be nicer, better, or healthier than employers adopting policies that give employees the resources, time and flexibility to take care of their families? What could be wrong with that? What grinch could object? The best reply to these questions is another bunch of questions: Do family-friendly policies promote equality between men and women, or the reverse? Are some family-friendly policies "mommy tracks" that encourage, enable, pressure and trap women (but not men) to adopt dead-end jobs and to sabotage their independence and their careers? Do family-friendly policies take the place of better solutions to the problems they are designed to help? Do such policies discriminate against employees who are not in a position to take advantage of them: single parents, childless single people, childless gay people, cohabiting heterosexuals, people with low wages?

Back in the days when few wives held jobs outside the home, lots of time and labor were dedicated to home tasks. Children had the full-time attention of a nurturing adult who was presumed to love them particularly. There was time for mom to make apple pie from scratch. Unfortunately, that devotion of time and labor were the result of a caste system: a portion of the population was designated at birth as restricted to a particular occupation, namely housekeeping. Caste systems produce big status differences, and this one was no exception: Women had distinctly inferior status. When a baby without a penis was born, they said, "It's a girl!", but they could just as well have said, right there in the delivery room, "It's a future housewife!" and "It's a person of very little brain, but real sweet!"

The movement of women, and particularly the mothers of young children, into paid work robbed the home of the worker who had been fully dedicated to tasks within it. Many, if not most, of these tasks are worthwhile, even necessary, despite the low status associated with doing them. Yet the march of women into the paid workforce was done without attention to how or whether the tasks they had previously done would be accomplished.

One reason for the pressure for family-friendly policies in companies—flexible time, job sharing, family leave to take care of a newborn or sick relative—has been the minimal change in the distribution of unpaid family work between spouses. More husbands benefit from the increased cash income from the paid work of wives, but they have not put out additional effort at home to any great extent. Wives also benefit from the increased income (and in some cases the increase in interesting activities and opportunities) but these benefits are partially counterbalanced by their greater workload.

One reason that husbands of employed women continue to withhold their labor from the tasks of running the household is the persistence of the ideology which declares certain tasks as appropriate for a person of a particular sex. Another is the low status associated with family work. Another is the still-discriminatory regime in the workplace, which deals men higher wages and better opportunities for promotion than women have, and makes the diversion of their energies and time to household tasks more costly. Another is wives' inability to enforce or motivate changes in their husbands' duties. Still another is the lack of public discussion about what the norm should be, and our failure to visit shame on those violating it. (Oddly enough, the first and only group not predominantly female to make a public issue of men sharing housework is the Promise Keepers, who also make a public issue of men being the bosses of their families.)

The low amount of male help has greatly increased the strain on the wife, as the time she has devoted to the performance of work (paid and unpaid) has increased, and her opportunities for leisure and sleep-time have decreased. This increased burdening of the wife has been the major source of demands for workplace policies that accommodate family life.

Most family-friendly policies are on their face sex-neutral; men as well as women can take advantage of the leave provisions, or use flexibility arrangements. This is also true of policies enacted since the Family and Medical Leave Act passed Congress in 1994, forcing companies with more than 50 employees to allow men and women to take time off—unpaid—to attend to a new baby or sick relative. In theory, family-friendly policies might have the effect of getting men to do more domestic work. But this effect is probably very limited, because these policies do little or nothing to counter the influences on male behavior that make men withhold their labor from household tasks.

Thus the major effect of family-friendly policies has been to allow wives to partially resume those abandoned duties, or facilitate her doing them; in other words, they have strengthened the traditional caste system (see "It's About Time," pp. 27-31). Workplace policies which provide the opportunity for part-time work are likely to have this effect, particularly if the part-time status means low pay and benefits, routine duties, and little chance for promotion. Husbands are less likely to take this kind of work, and the wives who do are cementing the inequality of their status. It is cemented further by paid parental leaves that extend well beyond the time necessary to overcome the disability caused the mother by the child's birth, and which are designed to allow the parent to engage in child rearing.

But workplace policies can take several forms, some of which might promote greater equality. Reductions in work time, for example, can be given as reduced daily hours rather than as additional days of vacation ("Comp Time vs. Overtime," pp. 38-39). More days of vacation may be used by the husband to go off fishing with male companions, or the family may spend more time at a summer cottage, where the wife continues to do all the domestic tasks. But if both spouses work full-time, a shorter standard working day would probably encourage both partners to share more family duties.

Requiring that both spouses share the leave associated with the birth (or adoption) of a child could be an important way to encourage equality. But the way governments have tried this so far—by requiring the father to take only a small part of the leave on pain of losing it—probably has little if any positive effect. In Sweden, for example, such leave is commonly used to lengthen a man's vacation. However, a series of leaves in which the mother and father alternated spells of several months could provide within-family care for very young infants in a way that would promote similar duties for both parents. A paid leave that gives a couple a constant fraction of their usual joint income, regardless of which parent was staying home at any particular moment, possibly subsidized by the government, would help to establish this pattern.

Family-friendly policies also can promote paid substitutes for unpaid family labor. Workplace subsidies for child care, or setting up child care facilities at the workplace, probably would promote equality because they relieve the family of a function usually carried on by the wife. However, we have to ask whether it is wise to push employers to provide these services voluntarily rather than push for better public provision. The history of health insurance in the United States suggests that when employers provide expensive benefits, it is far from universal, is subject to withdrawal, and may discriminate among different kinds of workers. And the very existence of even inadequate employer-based health insurance has stood in the way of developing a system providing universal coverage. Out-of-home child care is a task of the same financial and managerial magnitude; employer provision may end up being counterproductive.

One final concern about "family-friendly" policies is their effect on the absolute and relative status of single people, with or without children, and those not in jobs, all of whom are more likely to be women than men. Shortening the work day, with a proportional drop in pay, may make life more difficult for lower-income female single parents. The relatively hard-up single mother may also be shut out of costly benefits that both the (relatively affluent) employee and employer pay for (as happens with pension contributions where employers only match an employee's payment).

In general, "family-friendly" policies, like "family values," can push us back. We cannot assume them to be benign. Policies that help one group may hurt others. Policies that appear to make life easier for women, and that may even be welcomed by a majority of women, may cement women's inequality. The equity of such policies deserves close scrutiny.