Domestic Workers: A New Face of Solidarity

This article is from Dollars & Sense: Real World Economics, available at http://www.dollarsandsense.org

This article is from the

November/December 2024 issue.

Subscribe Now

at a 30% discount.

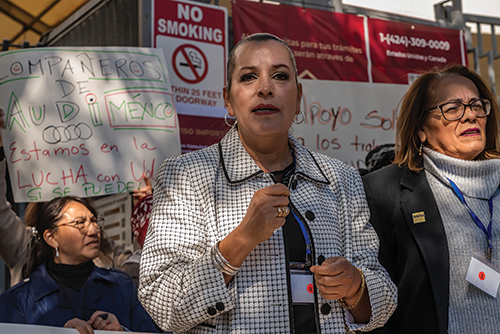

Domestic workers rallying in Los Angeles on behalf of striking workers at an Audi plant in Mexico, February 10, 2024. Credit: © David Bacon.

When it passed the U.S. Congress in 1935, the National Labor Relations Act recognized the collective bargaining rights of U.S. private-sector workers and established a process to require employers to bargain with their unions. The law carried a political price, however. Racist senators and congressional representatives in the Democratic Party, mostly from the U.S. South, demanded exclusions. Domestic workers, who were still largely African-American women, would not be covered. Neither would farm workers, who were mostly Mexican and Filipino immigrants in that era.

The Fair Labor Standards Act, passed three years later, gave private-sector workers the right to overtime pay and minimum wages. Again, domestic workers and farm workers were left out. In both Mexico and Canada they faced a similar exclusion. It is no accident that their labor rights and wages were held far below those of other workers in the decades that followed. Domestic labor therefore remained extremely precarious work done by women, and the low pay left their families in poverty.

Yet despite the exclusion, in the last few decades, domestic workers have sought to end their exclusion in all three countries. Yet despite the exclusion, in the last few decades, domestic workers have sought to end their exclusion in all three countries. That has never been an easy struggle. A new Trump administration, undoubtedly hostile to workers’ and immigrants’ rights, and the organizing efforts of women of color, will make this struggle harder. Solidarity among domestic workers across borders will be more important than ever.

In the United States and Canada, rising activism has accompanied the increase of immigrant workers in the domestic worker labor force. This wave of migration was in part the product of the displacement of families and communities in Mexico under the impact of the North American Free Trade Agreement, as it adopted neoliberal structural adjustment policies.

Global activism among domestic workers led to the adoption of a landmark international labor standard for domestic workers in 2011, the International Labor Organization Convention 189 on Decent Work for Domestic Workers (Convention 189), which recognized for the first time the right to minimum working standards for domestic workers. Following a campaign by an alliance of trade unions and domestic worker organizations, Convention 189 has since been ratified by 36 countries. The United States, however, isn’t among them.

The Covid-19 pandemic brought the plight of care providers into sharp focus everywhere. As resources in the care sector were already stretched thin, the situation worsened with thousands of experienced care workers either leaving the sector or losing their lives.

In the United States, Canada, and Mexico domestic workers have similar problems, but have taken different directions in trying to force a change. In the United States, passing a Domestic Worker Bill of Rights has been part of a national strategy. To date, 10 states and three cities have adopted it in some form, often including guarantees of paid time off, overtime, a requirement for written agreements, and protection against discrimination.

One major achievement of the statewide strategy was legislation in California that gave unions the right to bargain over wages paid to about 500,000 home care workers who provide care to people receiving support from the state’s In-Home Supportive Service Program. Two unions—the United Domestic Workers, a local affiliate of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Workers organized in 1977, and Local 2015 of the Service Workers International Union—were then able to negotiate wages for workers on a county-by-county basis.

Organizing a union for domestic workers has been the central strategy in Mexico, where the National Union of Domestic Workers (Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores y Trabajadoras del Hogar, or Sinactraho), was formed eight years ago. Pressure by that union has led to an increase in the rights and benefits of caregivers. While it has legal status and recognition, the union has no collective agreement, and focuses on individual contracts and organizing workers to defend their rights.

U.S. and Mexican organizations of domestic workers met in Los Angeles in February, earlier this year, in a conference organized by the UCLA Labor Center. According to Gaspar Rivera Salgado, director of the UCLA Center for Mexican Studies, “Our goal has been to create a space in which workers can exchange experiences and develop strategic planning for workers rights campaigns across borders.” A Canadian representative tried to come, but was denied a visa by U.S. immigration authorities. I conducted the following interviews during the meeting. —David Bacon

Norma Palacios (in red hat) with domestic workers rallying in Los Angeles on behalf of striking workers at an Audi plant in Mexico, February 10, 2024. Credit: © David Bacon.

Norma Palacios

Norma Palacios is one of the three general secretaries of the National Union of Domestic Workers (Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores y Trabajadoras del Hogar, or Sinactraho). Her parents were domestic workers, and she started doing the same work at 19 years old. She stopped working after the pandemic, but was a domestic worker until she turned 50 years old.

Last year we celebrated eight years of being established as a union, but we went through a training process for two years before that, which included a reflection on why we had to organize and what we could achieve. About 100 women participated. We organized and established Sinactraho so that we would have a voice, through our representation as a Mexican union at the national level. We complied with all the requirements and we are now functioning as a union.

In Mexico, the vast majority of the women are working for private people. Worldwide the conditions are not very different, whether there is legislation or not. Most do household work or domestic work, and many are indigenous women. Whether paid or unpaid, household work is devalued, and this has an impact on how it is seen, whether it is treated with dignity, and how household work is recognized. We have many strategies to organize ourselves for power, recognizing first that we are domestic workers, strong and powerful women, and then looking at how this work impacts society. Without our work, many of our employers would not be able to go to work.

We suffer from a lack of lack of labor rights, because in legislation in Mexico the value of this work is not recognized. Many of our colleagues suffer discrimination, even violence, and in the end we are left completely unprotected after having worked many years of our lives.

These are the main problems domestic workers have in Mexico, all due to the fact that this work is not recognized as work. By referring to it as “help,” it disguises the true relationships. Because we do not have a written contract, we have no right to a fair number of hours in a day, a fair salary, rights such as social security, vacations, housing, and to organize.

In Mexico, the regular domestic workers, that is, our coworkers who live in the workplace, which are the employers’ homes, stay with a single employer all week. Other domestic workers have multiple employers. Placement agencies are also an issue, basically outsourcing, because they negotiate wages and assign work, but without any labor protection.

Mexico has ratified Convention 189 of the International Labor Organization, which obligates it to comply with its protection of rights. This led to progress in legislation. The social security law was changed to give access to mandatory social security, but they don’t say when, or what will happen to employers who do not comply.

Workplace inspection in this sector is also a problem in Mexico. It’s a problem everywhere, and if it’s a problem in the automotive sector, you can imagine there’s even less for us as domestic workers, and that has an impact. That it makes it more difficult for us to make domestic work a decent job. There are many problems with wage theft. That led many domestic workers to organize ourselves. It is a process that takes time, because we have to go through a process of winning dignity, of recognizing ourselves, of assuming responsibility. If there is no commitment and responsibility to the organization, and to defending our rights, we will always have bad conditions.

We all fear that if we talk back to our employers, they will fire us, but that is what the union is for, to defend our rights. And we have had many success stories. Once we were established we created an advisory program, lawyers who help us defend the workers.

Government enforcement is not enough, and apart from that, there is a lot of ignorance about our labor conditions. The inspectors need to understand that household work is a job. But many people in government bodies are employers themselves, so logically they are not going to want to recognize our complaints. We still do not have a collective contract, but we are trying to promote the signing of an individual contract. There is a great lack of employers who want to sign them, however. And we have to train our colleagues so that they know how to defend themselves and establish that dialogue with employers.

I had the experience of having signed a written contract with an employer, but there is a lot of ignorance. In Mexico, the majority of workers belong to the informal sector, and there is not a lot of information available about why it is important to have a written contract.

We have to start from the right to organize in a union because that gives you power. It completely changes the panorama. Our coworkers have shown a lot of progress, regardless of the legislation that exists and its shortcomings. If you have to look for a change in legislation to be able to form a union, then do it. But in the meantime, we can’t stay here doing nothing. In Mexico we don’t precisely know how to force employers to comply and many workers are unaware that domestic workers are covered in this labor reform. On an international level, domestic workers need alliances. An alliance with our colleagues in the United States in our own sector would help us, because we are all workers.

Patricia Santana Bautista speaking at the rally for striking Audi workers, Los Angeles, February 10, 2024. Credit: © David Bacon.

Patricia Santana Bautista

Patricia Santana Bautista is a representative in the long-term care workers union, SEIU Local 2015, and an executive board member of the union. She represents nursing home and home care coworkers in one of the country’s largest union locals. In this interview she refers to the campaign of Claudia Sheinbaum for president of Mexico. Sheinbaum was elected in June by an overwhelming majority, and the line outside the Mexican consulate in Los Angeles of people waiting to vote was so long that the consulate ran out of ballots before half the people had been able to cast one.

This local union represents the people who lived and worked in the shadows and were not recognized for their work as in-home care providers. We take care of family members, of friends, and even many of our own children. Some take care of our husbands, mothers, or grandmothers. This was used as the reason for not recognizing our work as a job.

In reality, all of us care for a person who could be in a nursing home, or who has a medical condition that will last for the rest of their life. This work is very important and it gives people a life with dignity.

The vast majority, 90% of us, are women. We are Hispanic women and African-American women. Asian women are valuable members of our union because they cover so many languages. There is such a great diversity that our union holds all its meetings and does everything in seven languages: English, Spanish, Korean, Mandarin Chinese, and Tagalog. Armenian, too.

In our industry we understand that all people at some point, no matter their language or religion, eventually are going to need to use home care or long-term care.

Our union represents more than 400,000 home care workers at the state level. We are the largest local in our national union. Organizing has not been easy—it has been a struggle of many voluntary hours. It is a lot of work, but it is the only way to change lives.

The union negotiates on behalf of those 400,000 people, but membership is voluntary, not mandatory. That is, one decides to belong or not. But in many parts of our union 80% or 90% of the workers belong, because they understand the need. They understand that only by joining together can we win better contracts and representation. It is the only way we can get better benefits. In this industry the money that pays our checks comes from the federal government. They provide 56% of our income, the state government provides 32%, and another 12% comes from the county government.

That’s why we set up a fund, the CAF [Caregivers’ Action Fund], used only for political action. As members we sit down with candidates, talk to them, and see which ones support the values of our union. If they say yes to our fight, we are going to support them. Remember that more than 400,000 home care workers all vote. Generally the people we care for are American citizens. They can vote too. So can our family and friends. Every home care provider can impact three or four other people.

Doing the math, this means 1,500,000 or even 2,000,000 voters in California. That’s enough to make a candidate win or lose. That’s why we have to be organized and inspired, but above all well-informed.

Listening to the women from Mexico, I can see similar processes going on there too, because they have a federal union. It’s just that in Mexico it is handled a little differently.

Here we are not afraid to speak or sit down with any politician, to talk face to face. In Mexico gender violence is tremendous. If you want to talk with a politician, that can be an extremely large barrier. But today the candidates are more open to dialogue. It is historic because it has not happened for the last 100 years.

They are really very well-prepared people. They have the fighting spirit and are very inspiring. And best of all they have a real structure, a union. Despite the difficulties that exist at the political level in Mexico, they are super inspired. And we are faced with a simple reality—we all have the same problems, no matter where we live and work. Although we are in different countries, the problems are the same.

This year the presidents of both our countries will be elected. So this is something important we have in common. Now is the time to ask for what we need, and to present our agenda. If we don’t speak up now, when they are campaigning during this election period, we are not going to be able to make any changes. So now, when it is election time, it is time to speak, and it’s the time for them to listen more than anything. Every time we talk to a politician, we ask, “Once you sit in the seat of power, will you listen to us when we need you?” We don’t want you to get power and then forget who we are.

Just a month ago, Claudia Sheinbaum, the candidate for president in Mexico, was here in Los Angeles, and we were thinking about the same kind of process of making demands with her. I think Claudia Sheinbaum is someone who listens and has a strategy to assist our fellow Mexican citizens here in the United States. There are many of us. We are millions, really.

Within our own union there are many Mexicans. And really right now the presidential election in Mexico is very important to us as residents here in the United States, because we are citizens of Mexico too. Plus, we don’t forget our parents or our brothers who are in Mexico.

One of my sisters lost her sight, and my mother is 75 years old. So we have to support them because they can’t work anymore. So, really, although we are here, our heart is there too. We pay our taxes here, but we have to pay bills there too. Our income has to support two families.

So we are going to be mobilizing all of our people, especially because this is an election that should matter to all of us, both in the United States and in Mexico.

Vanessa Barba speaking at the Worker Solidarity in Action summit held on February 9-10, 2024, at the UCLA Labor Center in Los Angeles. Credit: © David Bacon.

Vanessa Barba

Vanessa Barba works for the California Domestic Workers Coalition. The Coalition includes groups that organize domestic workers who work for private employers, often in a family context.

In Mexico there is no state funding or federal or local funding to support home care. There are no home care programs or unemployment insurance. We have programs like that here. But the main difference between our situation in the United States and their situation in Mexico is the issue of immigration status. Here in the United States we are organizing domestic workers who don’t have a way to join a union because of citizenship and other barriers, so we’re scrambling to create a minimum wage, and to make sure people are getting it.

In the United States coalitions and organizations have concentrated on getting legislation, like the [Domestic Worker] Bill of Rights and civil rights. Through legislation many home care workers are employed through an arrangement that subsidizes the cost of care, and at the same time sets the wages for the workers. In Mexico women think the focus needs to be on organizing a union. They actually got legal recognition for a union for domestic workers in Mexico.

Women here who do home care in a home are advocating for a minimum wage, county by county, of about $30 an hour. Of course we support that, and we think everyone should have it. But it’s hard to have collective bargaining if you have individual people working for other individual people rather than an employer who employs a whole bunch of people.

So given those kinds of differences, how do we find the common ground to work with each other here in the United States and in Mexico? I guess the foundation of it all is to see domestic work as real work, a legitimate job, and to see the home as a workplace.

Valuing women’s reproductive labor in the home is the big picture. That requires cultural change, because everything stems from that. We need to make an argument politically that people deserve rights, and that those rights at work in a home can be enforced the way they can in another workplace. It all has to stem from seeing it as legitimate work and a legitimate workplace. We also have to recognize the status and the rights of women as women.

I’m excited about exchanging resources and materials, and I feel I’ve learned a lot. It was good to hear that unions in other industries can and do apply pressure through things like sanctions. I hope we’ve opened a door to conversations about more collaboration.

We need to get more concrete on what we’re advocating around things like health and safety. We need examples that work. We don’t have to recreate the wheel, and groups can rely on some of the work and materials that already exist in other countries. In Mexico, for example, they already have trainings and materials we could use here as we train workers to take care of their health.

When we organize women, we make it really clear that we’re not there to help anybody. It’s each individual’s responsibility to help themselves, and to empower each other by using an organizing approach rather than a service approach.

So on an international level, what is the bare minimum we’re all advocating? We’ve started talking about joint campaigns in both the United States and Mexico, with domestic worker groups working together on a common project. I’m not sure what it would look like, but we should try to imagine it.

Please consider supporting our work by donating or subscribing.