The Potential of Tax Reform in Latin America

This article is from Dollars & Sense: Real World Economics, available at http://www.dollarsandsense.org

This article is from the

July/August 2023 issue.

Subscribe Now

at a 30% discount.

It is well known that several countries of Latin America are among the most unequal in the world, in terms of both income and asset distribution. There are many political economy forces leading to such inequality, but what makes matters significantly worse in much of Latin America is that fiscal policy has effectively added to this by being both complex and regressive at the same time. As a result, in some of the major economies of the region, the distribution of disposable income (after taxes and transfers/subsidies) is hardly very different from the initial unequal distribution of pretax incomes. The important role of fiscal policy in generating better distributional outcomes is therefore lost.

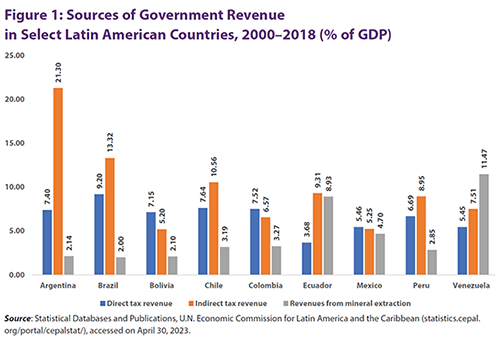

The good news is that, especially after recent political changes, some countries in the region are now actively seeking to transform fiscal strategy and particularly tax policies—to provide more crucially needed public revenues by shifting more of the burden to the rich and large corporations, who are more easily able to pay and have even benefited from recent economic crises. First, it’s necessary to provide some background. Many countries in the region are primary commodity exporters, and also derive a significant proportion of public revenues from royalties and dividends from the extraction of mineral resources, especially hydrocarbon exports. Figure 1 provides a breakdown of the share of direct and indirect taxes, as well as revenues from the exploitation of hydrocarbons and other mining, as a share of GDP. The data show the average of such revenues over 2000–2018, although as we shall see subsequently, the ratios changed substantially over this period.

Direct vs. Indirect; Progressive vs. Regressive

A direct tax is paid from the taxpayer directly to the government. The personal income tax and the corporate income tax are examples. An indirect tax is paid through an intermediary to the government. An example is the sales tax, where a buyer pays a tax to the seller, and that tax is then paid by the seller to the government. Direct taxes such as the income tax can be structured to be progressive, which means that the percentage paid to the to the government is higher for higher-income people than for lower-income people. But direct taxes are not necessarily structured to be progressive. An indirect tax, such as a sales tax, is generally regressive, which means that the tax is a lower percentage of the taxpayer’s income for high-income people than for low-income people. The sales tax is the same percentage of the amount of the sale for all buyers, but people with high incomes spend less of their incomes on items subject to the sales tax; thus, they pay a smaller percentage of their income through this indirect tax. —Eds.

Some countries clearly benefited much more than others. As Figure 1 indicates, for Venezuela and Ecuador, revenues from hydrocarbon and other mining provide more than double the revenues collected from direct taxes. But in general (and other than in Venezuela) however large the revenues from such mineral extraction activity, the revenues from indirect taxation were still greater. Meanwhile, revenues from direct taxation were generally much lower, other than for a few countries.

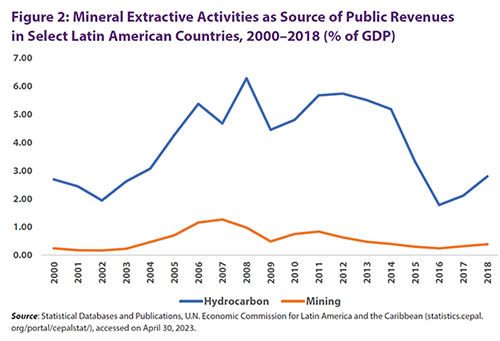

Of course, while mineral resources, especially hydrocarbon, can and have been an important source of public revenues, they have also been extremely volatile—not only because of changing domestic supply conditions, but more importantly because of sharp, often dramatic changes in global prices. Figure 2 shows how this has played out for the Latin American region as a whole, with big increases followed by declines. Despite the recent temporary revival of fuel prices, the medium-term and long-term trends are likely to be downward; and in any case it is definitely desirable for oil-exporting countries to wean themselves from fossil fuel dependence. This makes the need to identify more and better sources of progressive taxation all the more pressing.

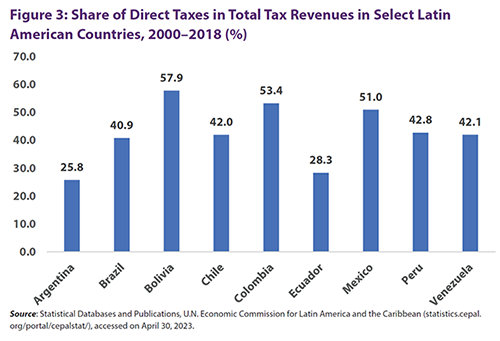

This necessity is highlighted by the fact that most tax systems in Latin America are regressive. One easy metric for this is the share of direct taxes in total revenues, since it is well established that indirect taxes generally tend to fall disproportionately on lower-income groups. The extent of regressivity can vary across income groups for direct taxation and whether and how much rates rise as incomes rise, as well as the specific nature of the indirect taxation and which types of consumption it falls on. But in general, a reasonable rule of thumb is that any tax system in which direct taxes constitute less than half of the total tax revenues is clearly regressive. Figure 3 shows the share of direct taxes in total tax revenues, and by this measure, most countries described here have regressive tax systems—although Bolivia, Colombia, and Mexico show greater progressivity. Argentina and Ecuador emerge as being especially regressive in taxation, and Brazil and Chile are also significantly below the halfway mark.

This is the context in which some of the “new wave” progressive governments in the region are attempting to reform tax systems and change revenue-raising strategies to correct this tendency. Perhaps some of the most innovative and promising proposals have come from Colombia, which enacted major tax reform legislation in December 2022. The changes are designed to increase tax revenues, prevent and reduce loopholes for tax avoidance, and shift the burden of tax payments to the rich.

For example, several sectoral corporate tax exemptions that did not have a clearly legitimate objective have been eliminated, and the statutory corporate tax rate has been increased by three percentage points. Taxes will be levied on the windfall profits of oil and coal companies depending on movements in international prices. The tax benefits that corporations can apply for have been limited to 3% of net income. A new 15% minimum tax for companies (which was agreed upon in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s “Inclusive Framework” on Base Erosion and Profit Sharing tax negotiations, albeit at a rate that is relatively low) will now be applicable with wider coverage than the GloBE (Global Anti-Base Erosion) rules, including all legal entities that pay income tax as well as all entities operating in duty-free zones. The concept of “a significant economic presence” that will enable taxation by local authorities has been introduced in the law, making it possible to tax multinational corporations that could otherwise avoid the tax net. Withholding taxes have been introduced for digital companies and increased for all companies. A surtax on the corporate income tax will apply to financial institutions (including insurance/reinsurance companies and commission agents), the coal and hydrocarbon sector, and the electric power (hydroelectric) sector. Dividend tax rates have been increased and a wealth tax has been reintroduced. In addition, there are some indirect taxes that target health and the environment, with taxes on sugary drinks and ultra-processed (junk) foods, as well as on the production of single-use plastics, and a carbon tax.

In Brazil, the new fiscal strategy that was recently unveiled appears to be conservative with regard to fiscal consolidation, which makes the need to raise tax revenues especially urgent. Current efforts on the tax front are oriented toward simplifying an extremely complicated and regressive system of indirect taxation that places heavy burdens on consumers as well as small and micro enterprises; the aim is to reduce the complexity and rationalize the taxes while ensuring that they move to a more progressive structure. There are proposals to address the problem of tax avoidance through transfer pricing by multinationals, especially e-commerce global giants, and to put curbs on corporate tax benefits.

Clearly, these are governments that can and should learn from one another in terms of the most effective tax strategies in a world in which the generation of domestic resources by the public sector has become more essential than ever. If these and other measures succeed, this will be hugely important for the economic prospects of the region. And it can provide valuable lessons for low- and middle-income countries across the world.

Please consider supporting our work by donating or subscribing.