The Che Marketing Moment

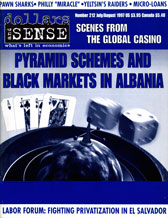

This article is from the July/August 1997 issue of Dollars and Sense: The Magazine of Economic Justice available at http://www.dollarsandsense.org

This article is from the July/August 1997 issue of Dollars & Sense magazine.

Revolutionary governments rarely enjoy personnel with advanced training, technical expertise or policy-making experience in the positions normally requiring them. The Cuban revolution elevated the Argentine-born guerilla leader and physician Ernesto 'Che' Guevara to the governance of the country's economic policy, on the basis of political rather than technical credentials. His tenure as Governor of the National Bank and, later, as Minister of Industry was fraught with difficulties, associated with an overhasty effort at industrialization in the early 1960s, and then an exaggerated turn back towards sugar production. It also, however, included debates over economic policy which really confronted the greatest issues facing the revolution—what should Cuban society become, and what are human beings capable of becoming?

What makes this newsworthy is the Che Guevara craze now accompanying the thirtieth anniversary of his death. Besides five new biographies and six new films chronicling his life, his image can also be found on a new line of "Revolution" skis from Fischer and a new watch from Swatch, along with the usual T-shirts and posters. With the Cold War supposedly over (though U.S. policy towards Cuba remains on a Cold War footing), and with the "threat" of revolution in Latin America receding, Guevara has been transformed into a harmless pop-culture icon. Alternately portrayed as a free-spirited hippie, a touchy-feely romantic, or an idealistic but basically quixotic adventurer, he has been "softened," in the words of the New York Times' Doreen Carvajal, "from a rebel with a cause to a rebel with a heart."

Che Guevara the economist has, unsurprisingly, not figured much in the recent craze. In part, this is because economics is thought of as boring and stuffy, ill-fitting a dashing figure like Guevara. In part, it is because his economic thought illuminates his cause, and that is not what the pop marketing of his image is about. Between 1963 and 1965, Guevara was a key participant in what became known as the "great debate" over economic policy in Cuba. The most important issue was how to motivate individual productive effort. Guevara believed that offering material incentives would only promote a materialistic way of life. The Cuban government should, instead, promote altruism and dedication to the revolution as motives for productive effort—and as a means to a "revolutionary way of life."

Today, these ideas may seem hopelessly idealistic, even quaint. For Cuba in the 1960s, however, they were the spirit of the age. The most successful effort to activate "moral incentives" was the 1960-1961 literacy campaign. Aimed at the eradication of illiteracy in Cuba, it mobilized hundreds of thousands of urban volunteers, many of them teenagers, to go to rural areas and teach. Like the revolutionaries who went to the mountains to fight against the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, the young literacy volunteers went to the mountains to fight the "Battle of the First Grade," and emerged victorious, marching into Havana at the campaign's conclusion in a mood of triumph and exhilaration.

When Cuba's popular militias stopped the U.S.-sponsored exile invasion at the Bay of Pigs in 1961, Che Guevara was impressed not only by the armed resistance to the invaders, but also by the ability of popular initiative to cut through economic problems like bureaucratic red tape and absenteeism. Guevara felt this experience confirmed the potential of moral incentives, though he recognized that it was easier for these motives to emerge in life-and-death moments than to become the stuff of everyday life. In this latter respect, the Cuban revolution was less successful. The failure of the 1970 sugar harvest to reach the stated goal of ten million tons, despite a massive mobilization of volunteer labor for that purpose, marked the end of this idealistic period in Cuban history.

By then, Che Guevara had been dead about three years, killed trying to duplicate in the Andes the revolution which he and his comrades had gone into Cuba's Sierra Maestra mountains to ignite. After Guevara's death, Susan Sontag wrote, "Che must not be allowed to become an inspiring 'beautiful' legend. Far more useful would be to stress his singularity, Che as a controversial figure on the contemporary revolutionary scene." He certainly was too controversial to fit comfortably on a pair of skis or a watch. The Guevara that people are buying today has been downsized for a cynical age.