Trump's Lump of Coal

The trade deficit is the world’s Christmas gift to the U.S.; Trump’s tariffs substitute a lump of coal.

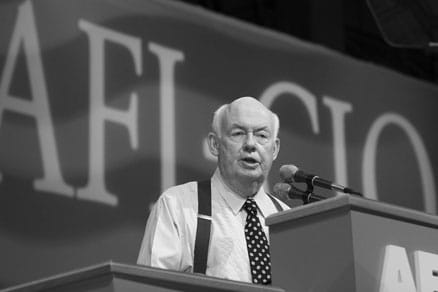

AFL-CIO President John Sweeney at the federation's convention in July. Photograph by Jim West.

Teamsters President James Hoffa at a July 25 press conference to announce disaffiliation from the AFL-CIO; SEIU President Andy Stern is at left. Photograph by Jim West.

No doubt this July's decision by the leadership of the Service Employees International Union and the Teamsters to walk out of the AFL-CIO and form an alternative labor federation, Change to Win, underlines the severe problems the U.S. labor movement faces today and the absence of clear answers as to how to move forward. But what does the split really mean? Can either side legitimately claim the support of progressive labor activists? How new is Change to Win's program--and what are its likely results? We invited a number of longtime labor activists and scholars to help sort it all out.

Issue # 261, September/October 2005