Health Insurance for 20 Million is at Risk

If Congress fails to renew the ACA enhanced benefits, millions will be unable to access the health care they need.

How Elon Musk used government loans and subsidies to enrich himself.

Back in 2009, the Obama administration announced $8 billion in loans to car companies to encourage the production of vehicles powered by electricity for cleaner air. At the time, automobile firms were in extreme distress due to the Great Recession. Ford had a $14 billion loss in 2008, Nissan reported losses in 2009, and fledgling Tesla was so close to failure that Elon Musk agreed to sell 10% of it to Daimler (now known as the Mercedes-Benz Group AG) in Germany. Obama’s Department of Energy loaned Ford the bulk of the money, $5.9 billion, to retool 11 factories; the Japanese car manufacturer Nissan got $1.9 billion to upgrade its Tennessee plant. And $465 million went to Tesla.

Tesla was then considered a start-up that had produced only a novelty car called the Roadster, which cost over $100,000. The ultra-wealthy thought it was cool and fast, and Musk hoped to expand to mass production of a less expensive electric vehicle (EV) called the Model S. A 2012 Tesla press release advertised the new model with a base price of $57,400, but Wall Street Journal reporter Tim Higgins, in his book Power Play: Tesla, Elon Musk, and the Bet of the Century, says that in 2013 it was retailing for $106,900, “a number that was staggeringly more than the $50,000 price tag Musk had promised when he first revealed the vehicle in 2009.”

President Barack Obama’s $465 million loan allowed the EV maker to transition from a novelty car company to mass production and made Musk richer than rich. In 2004, Musk was an early investor in Tesla (founded 2003), and in 2007 he pushed out one co-founder of the firm, Martin Eberhard, while the other co-founder, Marc Tarpenning, left in 2008. By 2009, Musk had put less than $100 million into Tesla, while Daimler had purchased 10% of the company for $50 million—which means that the U.S. government was the primary investor in Tesla when it moved from being a fragile start-up to a viable manufacturer. Despite the largesse of this Democratic administration, in 2024, Musk bought considerable influence with Trump’s campaign with more than $250 million in donations. What led him to invest more into Trump’s second presidential bid than his initial investment in Tesla? The short answer is that Musk wants to advance his goal of making sure no other automaker produces a competing EV.

A signature aspect of the 2009 bailouts was that policymakers were ideologically averse to taking equity stakes in private corporations, be they banks or auto companies. Yet by giving public money to for-profit entities with few strings attached, the government helped to create very large entities that have since run amok. Adam Smith warned us in 1776 that if the government gives favors to one firm, it risks creating a monster in the form of a monopoly with which no unfavored firm has a chance to compete. As a result of government favors, Tesla was able to dominate the EV market for over a decade. Then, in 2022, Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act, which aimed to reduce inflation, cut carbon emissions, and improve Medicare. The legislation was the largest investment in clean energy in U.S. history, and its focus on encouraging legacy automakers in the United States to increase EV production put the Biden administration on a collision course with Musk.

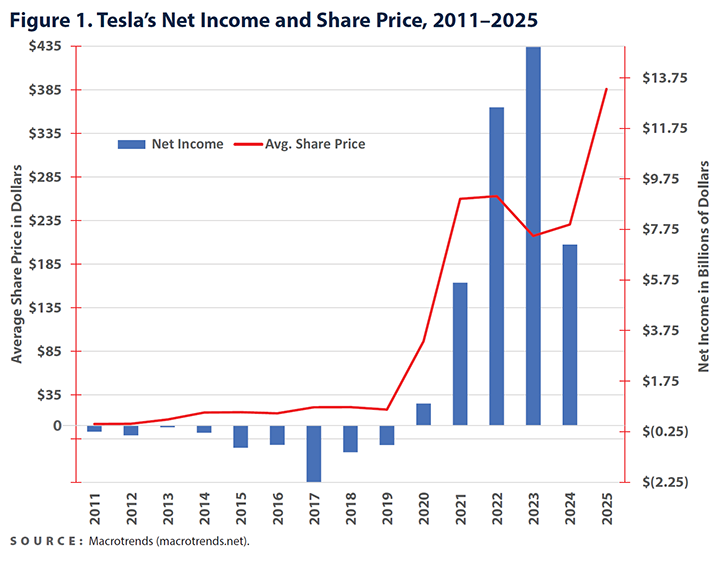

For the last nearly 25 years, I’ve taught economics at a state school where most of the students come from modest circumstances. My business students admire Musk’s ability to make his share price rise no matter what the success of his cars (note in Figure 1 how the share price has risen in the past year despite the serious drop in net income). These mostly young men have worked overtime to come up with a few thousand dollars to invest in Tesla and crypto. When their Musk-related trades come out right, they come out with double the money and a sense of pride in their investment skills, so they experience the kind of self-confidence that is hard to come by at age 21 in the United States in 2025. When wages are too low to allow one to save, and one cannot obtain an education without taking on tens of thousands of dollars in debt, then doubling or tripling your wealth through high-risk bets seems like a way out. Tying oneself to someone who successfully rigs bets is attractive. Indeed, the mindset of my students is only an extreme variant of the sentiments of every American with a 401(k).

U.S. government promotion of revolutionary technology is not new. Consider President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s development of the Hoover Dam and his efforts to bring electricity to Appalachia. Particularly in the post-World War II era, the U.S. government has invested in early-stage ideas—by providing businesses with public venture capital—while private money tends to invest at a later stage. One example of government investment is the Tennessee Valley Authority’s machine tool lab, which in the 1950s poured money into designing precision lathes to shape soft uranium shells on nuclear bombs. The government then reached out in the 1960s to promising engineers in the Connecticut River Valley and asked them to develop commercial applications for the technology—leading to the commercial diamond turning machine in the 1970s, which resulted in dramatic cost reductions in producing plastic contact lenses. Today, diamond turning machines are used to make affordable camera lenses for cell phones, and to make layers of touch screens. (See Marie Christine Duggan, “Reindustrialization in the Granite State: Diamond Turning Innovation in the Age of Impatient Finance,” D&S, November/December 2018.) As the economist Mariana Mazzucato has explained in her book The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths, Apple’s iPhones were only “smart” because the U.S. government developed Global Information System (GIS) technology and the internet.

After the financial crisis of 2007–2009, there was talk that the U.S. government should invest in manufacturing as a counterweight to the private financial sector and should particularly push innovation in clean energy. In hindsight, the trick was to assist innovative firms without letting them profit at the taxpayer’s expense, and that is where the U.S. government dropped the ball. To take an example from a different industry, U.S. pharmaceutical innovation has been financed by the U.S. government via the National Institutes of Health, but after the financial crisis, pharmaceutical firms shoveled even more profits to shareholders through overly generous dividends and stock buybacks. One of the side effects of public investment may be a tendency for private companies to look to political machinations as the means to make their bets on the future direction of technology come out right.

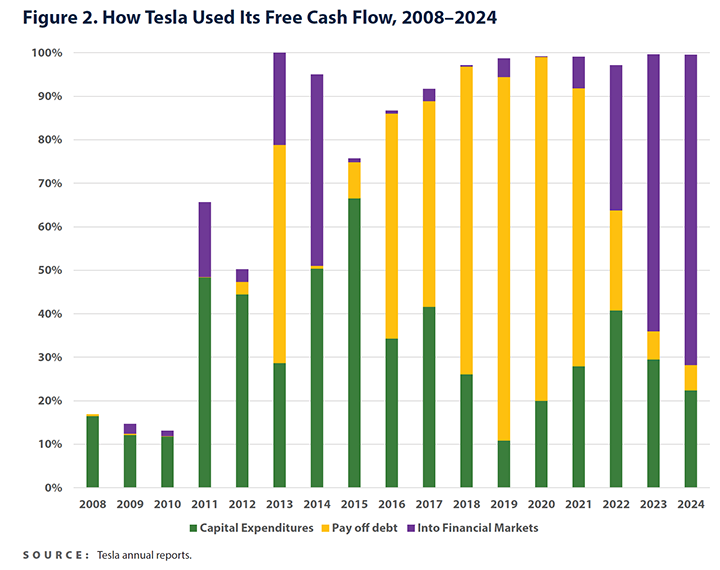

If Tesla had not repaid the Department of Energy, then the government would have received three million shares in the company. Yet, as Mazzucato points out, it would have made more sense for the government to receive shares in Tesla if the company was profitable. Private venture capitalists often retain 80% of a start-up investment’s profits, and then as the firm is sold into the stock market, the venture capitalist makes enormous profits with stock price appreciation. In 2014, Daimler sold the $50 million Tesla stake it had purchased in 2009 for $780 million. Musk prioritized paying back the Obama administration loan over accumulating capital at the company because that was the way to keep total control of his company. Figure 2 shows, in the yellow parts of the bar for 2013, Tesla using its free cash to pay back the loan. If the government had received the rate of return that Daimler made, Tesla’s success would have enriched the public. Instead, when Tesla’s stock price took off in 2019, it was private shareholders who reaped the enormous benefits of the government’s investment, and of course, Musk is the largest individual shareholder in Tesla.

If we examine Tesla’s capital expenditures as a percent of total spending in Figure 2, we see that the company prioritized investment in plant and equipment (capital expenditures) between 2009 and 2015—the years following the Department of Energy loan. Capital investment was about 50% of free cash flow prior to 2015, but that percentage fell to roughly 25% for the 2019 to 2024 era. How has Tesla spent its money in the past five years? The firm was spending over 50% of its free cash on investments in financial markets, as shown in the green bars of 2023 and 2024. Indeed, in 2021, financial investments of Tesla’s free cash included a $1.5 billion bet on crypto currency.

The fact that in 2023 Tesla put more than twice as much money into financial markets as it did into capital equipment for production raises a red flag. One can argue that investing one’s funds into

interest-bearing instruments is smart, since Tesla could even earn profits on those financial market bets that would facilitate manufacturing. However, a pattern of putting more into financial markets than into manufacturing suggests that the returns from bets are higher than returns from capital accumulation. It is odd that at a time when Tesla began to face fierce competition, it did not invest more into innovation, given that it had the funds available. The diversion of funds into bets rather than capital accumulation is not unique to Tesla; plagued the U.S. economy between 2010 and 2020. For example, Boeing’s enthusiasm for betting on its own stock price reduced its accumulation of capital for making planes for a decade, such that the firm’s manufacturing process became more and more precarious. (See Marie Christine Duggan, “Boeing Hijacked by Shareholders and Execs!”, D&S, July/August 2021 and “As Boeing Cracks, Is It Capitalism or Kafka?”, D&S, September/October 2024.) These examples give proof to an insight from the 20th-century economist John Maynard Keynes: We are in trouble if speculative investments divert from real capital accumulation.

The trade-off between profits from bets versus profits from producing useful objects is something Keynes wrote about in the 1930s, when he famously said, “Speculators may do no harm as bubbles on a steady stream of enterprise…[but] when the capital development of a country becomes a byproduct of the activities of a casino, the job is likely to be ill-done.” By “speculators,” Keynes meant people who buy an asset in hopes that it will appreciate—assets such as crypto. “Capital development” is creating physical plant to produce useful items for humans. Keynes is therefore saying that if executives rely on profiting from bets in financial markets to raise the funds for investment in manufacturing, the process of capital accumulation will erode. He, too, lived through a period (the 1920s) when speculation in markets (in his case, in exchange rates) was far more exciting than making actual products, but this made the global economy susceptible to collapse, contributing to the U.S. stock market crash of 1929 and the European banking crisis of 1931.

Once the bets are placed, companies have a clear incentive to make them increase in value by appealing to political actors. Consider, for example, that Tesla has prioritized developing self-driving technology. The software has been involved in hundreds of crashes since 2016, and in 2021 the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) ordered car manufacturers to report all crashes involving self-driving technology. In 2024, the Wall Street Journal managed to extract videos from 222 totaled Teslas to ascertain why the cars had crashed. Autopilot veering explained 20% of the crashes, and failure to detect an obstacle blocking the road explained 14% of the crashes, which were at times fatal. In some cases, as reported by the NHTSA, if the undetected obstacle is another vehicle broken down on the side of a freeway, the Tesla crashing at full-speed might have also hit first responders assisting at the scene.

In December 2024, just as Musk’s support for the Trump campaign reached fever pitch, the transition team recommended eliminating the requirement that auto companies report fatal crashes while using autopilot to the NHTSA. Of course, by eliminating the reporting requirement, the catastrophic failures of the technology will be less likely to impede Tesla’s share value. As we go to press, Musk has recently made major cuts at the NHTSA, reducing the number of staffers in charge of the oversight of self-driving cars from six to three.

Mary “Missy” Cummings is a systems engineer who has repeatedly spoken out against Tesla’s self-driving technology. As a safety advisor for the NHTSA from 2021–2023, she made it clear that she faults Tesla for cutting corners by heavily relying on cameras, with little use of radar, and no use of Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) in its self-driving system. The “light” in “LiDAR” refers to lasers, which are used to assess the distance between the car and objects, and it is the top technology of our day. Camera systems are more likely to fail when an object is difficult to see, such as an overturned tractor trailer on a freeway at night. The fact that Tesla’s autopilot usually works lulls drivers into a false sense of trust in self-driving technology.

In 2022, Musk unleashed a Twitter mob on Cummings for her work at the NHTSA—and she even received death threats. Since the company has no plans to release a new model, Tesla’s high stock price can only be justified if Tesla gets a fleet of driverless robotaxis onto city streets, as Musk plans to do by June 2025 in Austin, Texas. Cummings, who is also a former Navy fighter pilot, now teaches cybersecurity and robotics at George Mason University. The families of crash victims know she will remain outspoken about the dangers of Tesla’s self-driving technology.

The Silicon Valley disruptor mentality is that founders of start-ups are geniuses so superior to legacy manufacturers that they alone deserve to reap the rewards from their dominant positions, and that wiping out legacy businesses is the type of “creative destruction” that propels progress. The Biden administration had a different vision: offer financial incentives to entice legacy manufacturers to rapidly move to producing electric vehicles in the United States while also supporting the United Auto Workers’ (UAW’s) strike so that the hundreds of thousands of workers in those industries would share in the rewards of EV expansion.

The Biden administration’s push to rapidly increase EV production came in the form of incentives built into the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), and the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act. The IIJA provided $43 billion to extract lithium, cobalt, and other minerals in the United States for EV batteries and to then manufacture the batteries in the United States. As a result, EV battery manufacturing in the United States increased tenfold between 2021 and 2024. The IIJA also provided $7.5 billion to build 500,000 charging stations for electric vehicles. The IRA included $47 billion in tax incentives to consumers to purchase zero emissions vehicles (EVs or hybrid cars). The CHIPS Act earmarked $2 billion for increased manufacturing of semiconductor chips in the United States. The average electric vehicle includes 10,000 microchips, and this investment in manufacturing capacity would make it possible for U.S. companies to be less reliant on chips that are made abroad.

In 2021, 72% of the electric vehicles sold in the United States were Teslas. By 2024, Tesla’s U.S. market share fell to less than 50% for the first time since 2017. While there were plenty of reasons for Tesla’s decline—including increased competition from foreign EV manufacturers and an aging product line—increased competition from legacy manufacturers here in the United States certainly played a role.

With the IRA, the Biden administration’s aim was for 40% of the vehicles on the road to be zero-emission by 2030. Incentives to firms to build such vehicles would in theory bring down prices and slow climate change. Consumers can also receive an incentive (a rebate of up to $7,500, as mentioned above) if the vehicle is assembled in the United States, 50% of the components of the vehicle’s battery are produced in the United States, and 40% of the critical minerals used in the vehicle (e.g., lithium for batteries, but also copper and cobalt) are produced in the United States or in a country with which the United States has a trade agreement. These percentages were set to rise over time: by 2028, 90% of the components of the vehicle’s battery would need to be manufactured in the United States for the car to qualify for the rebate.

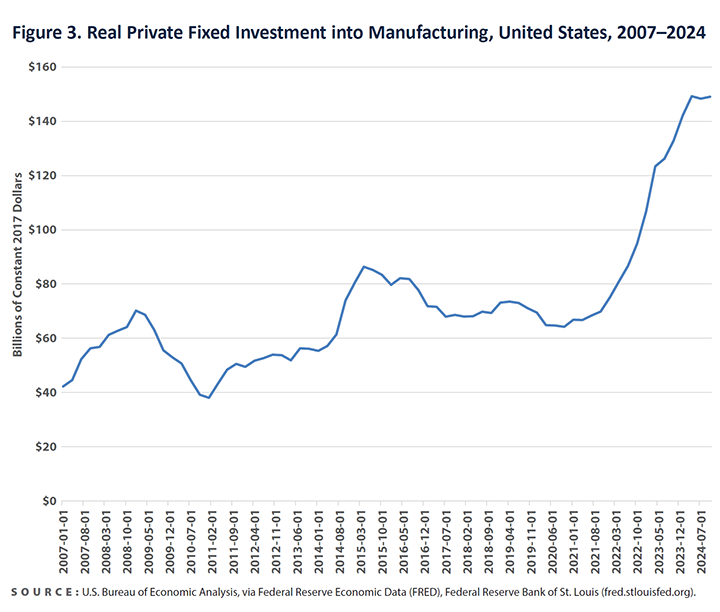

The reason that the Biden administration insisted that 50% of battery components be made in the United States is that battery innovation is what will ultimately increase the driving range of EVs and push manufacturing costs down. The government’s goal was to make sure that this innovation would occur in the United States and not abroad. In response, Tesla did relocate production of some of its batteries from Germany to the United States, as did other manufacturers. Indeed, the dramatic increase in fixed investment, i.e., capital accumulation, during the Biden administration’s four years was beyond anything I have seen in my lifetime, as shown in Figure 3. There is a lag between fixed investment and job creation, and the job creation from such investments was only barely beginning by the time Biden left office. Between 2007 and 2020, U.S. investment

in manufacturing never exceeded $85 billion per year (in constant 2017 dollars), and in the short span of two years after the IRA and the CHIPS Act passed in 2022, real investment increased to roughly $150 billion per year. Now that is capital accumulation.

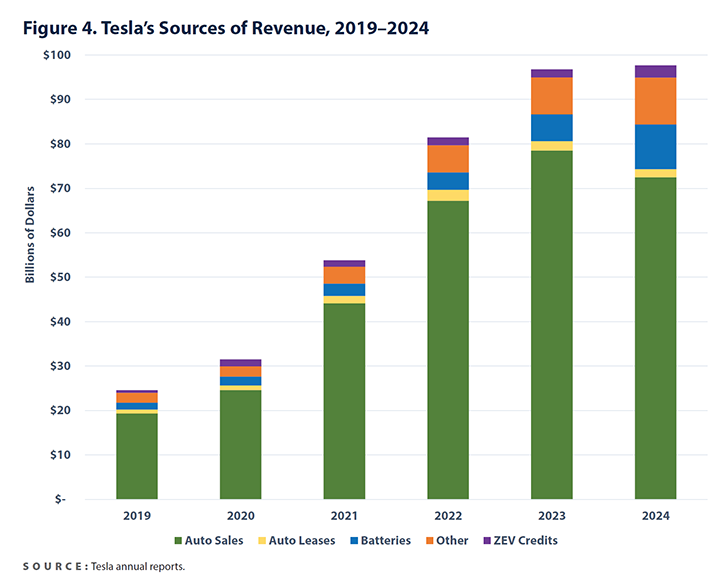

A major incentive to produce electric cars comes from the 12 states that mandate that a certain percentage of each manufacturer’s cars must be “zero-emissions vehicles” (ZEVs), a designation that includes EVs as well as hybrids. Manufacturers are credited for these sales in each state, but it is not so simple as one sale being equivalent to one credit. The driving range of the vehicle determines the ZEV credits, so that each Tesla (which has an extended range) tends to earn over four credits. Sales outside of ZEV states do not qualify, which is why sellers tend to offer more EVs in states such as California, New York, Massachusetts, and Vermont. Tesla earns far more credits than it needs and sells its oversupply of credits to manufacturers that do not produce enough qualifying vehicles.

Tesla’s sale of ZEV credits has turned into quite a windfall of free taxpayer money for the manufacturer: around $600 million in 2019, then around $1.5 billion in 2020 and again in 2021, over $1.7 billion in 2022 and again in 2023, and then $2.7 billion in 2024. As Figure 4 illustrates, sales of ZEV credits are a small percentage of Tesla’s overall revenue, but they can have a big impact on share prices. Consider that in 2020, the year that Tesla’s share price rocketed because net income was finally positive, the revenue from Tesla’s sale of ZEV credits helped push the firm over the edge into profitability. This was free money for Tesla that made it look like the company was well into the black, as opposed to still in the red or just barely pulling out of it.

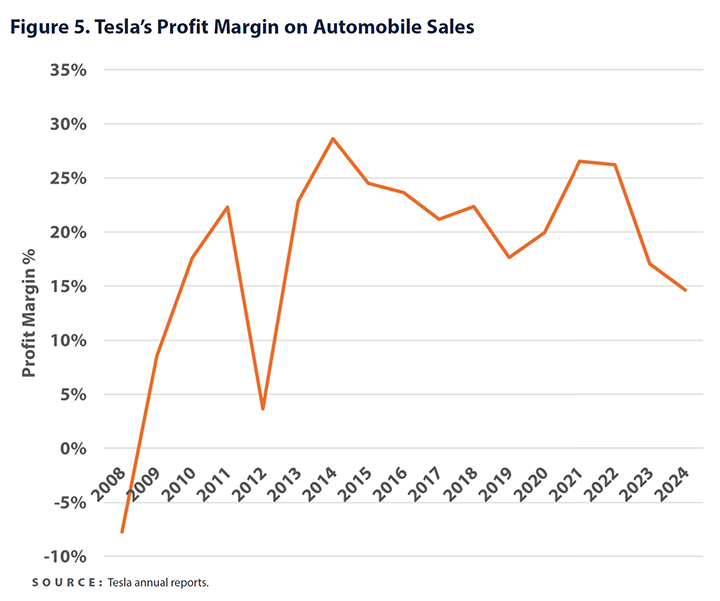

Between 2021 and 2024, consumers saw their choices for EVs increase dramatically. Several manufacturers ramped up production more than tenfold: Cadillac went from selling 231 EVs in 2021 to over 29,000 in 2024. BMW, Honda, and Rivian had the same explosive growth to tens of thousands of vehicles sold each year. In 2023, Tesla responded to the sudden competition by reducing prices, which is what Adam Smith would predict. Yet one gets the sense that Tesla was not just enticing customers with these cuts, but also seeking to destroy its competitor. For example, Ford manufactured the first version of its F-150 Lightning electric pickup truck in April 2022, while Tesla’s Cybertruck came out in 2023. Ford’s F-150 Lightning won over skeptical insiders when it won the 2023 Motor Trend’s award for truck of the year. The increased supply resulted in lower sales for Tesla. The Cybertruck retails for between $79,000 and $99,000, depending on options, while the Ford F-150 Lightning has a suggested price range of $49,000 to $87,000. As we go to press, Tesla is offering a $6,000 discount on its truck. Because Tesla had been solely producing EVs for over a decade, the firm had lower costs than its new competitors, who were ramping up production. In an attempt to compete with Tesla, Ford offered a $2,000 discount, free charger installation, and 0% APR financing for 36 months, which meant that Ford was selling the car at a loss. The legacy automaker halted production on the F-150 Lightning in Dearborn, Mich., in October 2024. Tesla’s incentives also cut in on Tesla’s profit margin, which fell from 26% in 2022 to 15% in 2024 (as you can see in Figure 1). Nonetheless Tesla is currently obtaining positive profits, while Ford lost billions on its EV production in 2024. Furthermore, the 50% drop in Tesla’s net income between 2023 and 2024 had little impact on Tesla’s share price, as Musk’s choice for president was inaugurated. It is a tragedy for Dearborn, Mich., to see the Ford F-150 Lightning plant suspend production. The tragedy is particularly acute given that the UAW had successfully fought to unionize EV transition jobs in 2023.

While Musk was doubling down on self-driving technology as the way for Tesla to pull ahead in profits, he seems to have lost sight of the fact that 40% of an EV’s cost is the battery. Batteries are a key EV component, and innovation in battery technology fundamentally drives the quality and price of electric vehicles.

Tesla outsources the chemical process of producing battery cells to a range of companies, including the Japanese company Panasonic for the battery packs assembled at its Nevada factory; the Korean firm LG Chem and the Chinese company Contemporary Amperex Technology Limited, better known as CATL, for battery packs made at Tesla’s Shanghai factory. In 2022, Tesla’s Berlin-Brandenburg factory sourced complete batteries from the Chinese company BYD. BYD (whose name comes from “Build Your Dreams”) introduced a lithium iron phosphate (LFP) battery in 2020 under the trade name “Blade.” Conventional lithium-ion batteries have a tendency toward “thermal runaway” (in plain English, they overheat with the potential to explode). LFP batteries do not suffer from thermal runaway and are therefore a significant advance in safety. Furthermore, as the name suggests, the Blade is flatter than a traditional lithium-ion battery pack, which permits better thermodynamics in vehicles using LFP batteries. And for those of us living in cold-weather climates, charging LFPs does not slow down as much in the cold as does charging lithium-ion batteries. Finally, LFPs allow longer driving ranges and more powerful bursts of energy. In short, BYD innovated.

In 2023, BYD arrived on the global scene with high-quality electric vehicles that are significantly cheaper than Tesla’s. BYD is a vertically integrated company, so the knowledge to produce its Blade battery and its semiconductors is in-house. Vertical integration makes BYD an expert in battery cell chemistry and hence well-placed to innovate in that key component of an EV. Vertical integration also keeps costs down, as there is no markup paid to a supplier.

But where the BYD models especially impress is at the lower end of the price range. The BYD Dolphin rivals the Tesla Model Y, but costs considerably less. Price comparisons are a bit difficult because BYD cars are not sold in the United States. But in Malaysia in 2024, the BYD Dolphin sold for half the price of a Tesla Model Y (the 2025 Model Y has a starting price of just under $45,000). The BYD Seagull, which is smaller than the BYD Dolphin and designed to be cost efficient, sells for around $11,000 in China. At that price my students could certainly afford one. At the high end, the price gaps are smaller, but what is remarkable is that BYD can make as good a luxury car as Tesla. In 2024 the BYD Seal Premium competed with the Tesla Model 3, both hovering around $60,000. Now all BYD models come with self-driving technology installed, and the high-end models have the LiDAR detection system that Tesla has eschewed. Tesla has not released a new car since the Cybertruck in 2023, while BYD has launched several new models over the last couple years.

Like the Obama administration, the Chinese government in 2009 began promoting zero-emissions vehicles. In that year China offered an $8,800 rebate to taxi companies that purchased EVs or hybrids, and in 2010 China made ZEVs exempt from annual taxes and license-plate fees. China has mandated that by 2030, 40% of new sales should be EVs. Between 2020 and 2021, China’s EV sales doubled from 5.7% to 12%, so the plan appears to be on track. In 2020, the Chinese purchased 1.1 million electric vehicles. The top-selling EV in China in 2022 was the Hongguang Mini, a two-door car which retailed for $4,500. It is produced by a joint venture between a state-owned company and General Motors. (Since 1994, a Chinese law mandates that foreign auto companies must have a local partner with 50% ownership in order to sell in China.) BYD’s Han sedan was the third best-selling EV in China in 2022. (Warren Buffett owns 8.5% of the company.) In 2019, Tesla managed to get around the 1994 rule by opening a wholly-owned factory in Shanghai’s new Free Trade Zone, though later Tencent Holdings purchased 5%, and by 2023, Tesla Shanghai was using Chinese-made CATL batteries.

But Tesla’s fortunes in the Chinese market have been declining. In 2021, Tesla produced some 473,000 cars in China and sold two-thirds in that country. In 2021, high-profile problems with Tesla’s braking system and several crashes were major news in China. Furthermore, in 2021, the Chinese government began phasing out subsidies of $2,500 to $3,500 for vehicles with the Tesla range, and instead followed the model California pioneered where ZEV producers sell credits to non-ZEV producers. Even so, Musk won good will in China when he resisted the pressure in the first Trump administration to bring manufacturing back to the United States. In 2024, BYD’s safer Blade battery, its entry-level cars, and its high-quality luxury models rocketed that Chinese EV maker ahead of Tesla in China’s market, and BYD is expected to overtake Tesla in global sales in 2025.

Tariffs, whether under Biden or Trump, make it less likely that less expensive EVs will reach U.S. consumers. In May 2024, the Biden administration increased tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles from 25% to 100%. Certainly, tariffs on Chinese cars do increase the chances of a profitable transition to electric vehicles for U.S. automakers. However, Tesla is the greatest beneficiary, even though its workforce is nonunion and the company has long been at odds with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration over workers losing parts of their fingers and receiving chemical burns. Furthermore, Musk stated in 2024 that he has no interest in producing an inexpensive electric car. The BYD Seagull would offer humble people an alternative to the Chevy Volt, which struggles to hold a charge in colder climates.

Economists traditionally favor tariffs to protect infant industries. But tariffs are a double-edged sword because prohibiting consumers from purchasing a better car also has the potential to hold innovation back. If U.S. consumers cannot purchase a BYD Song, then there is less incentive for Tesla to invest in improvements to their Model Y for the U.S. market. Wang Chuanfu, CEO of BYD, earned about $1 million in 2020, while according to Forbes, in 2020 Musk earned $11 billion, or 11,000 times as much. In 2023, Tesla produced 1.8 million EVs, to BYD’s 1.6 million. Customers in Europe, Australia, and China are favoring BYD, and most industry experts expect future growth to favor BYD and other Chinese manufacturers.

Adam Smith warned us in 1776 that if government grants favor to a single firm in an industry, a firm with monopoly power will emerge. This firm will have no incentive to lower prices for consumers or to care for the workers that are the source of its product. Smith was thinking of the British East India Company, which by 1765 was not only selling tea at high prices within the British Empire but also burning rice fields in Bengal to push up the price of food for its workers—causing a tragic famine. Everyone in New England knew this story of rapacious cruelty carried out by a shareholder-owned company with government influence, and Samuel Adams and John Hancock organized the Boston Tea Party in 1773, which dumped East India Company tea into Boston Harbor and galvanized the population to break free from Great Britain.

Perhaps no nation can make the leap from combustion engine to green energy without government support, but the moral of this story is that governments have to be careful that the subsidies they provide do not lead to private accumulation by a handful of individuals.

While I dream of owning a red electric Ford Lightning F-150 pickup truck, my modest salary keeps that dream from becoming a reality. You could only get the Biden tax rebate if you paid at least $7,500 in taxes per year. That pretty much ruled out any of my students—and it ruled me out, too. The day after the election, I dropped off my gas-guzzling 2017 Subaru with the mechanic. He is a master at his craft and delivers the unvarnished truth about repairs with a steady gaze and absolute honesty. “That Elon Musk invested more than $250 million in the president-elect,” I said, “the electric car must be coming.” Suddenly, I had the feeling that all eyes in the garage were on me. It being rural New Hampshire where the general sentiment is that Democrats don’t like us, I knew many had voted red. Until then it hadn’t occurred to me that some people may have voted for Trump because they believe he will restore the combustion engine to the center of U.S. culture. The master mechanic looked at me quizzically and reminded me they don’t charge well in the cold New England winter. He didn’t think the electric car would take over any time soon.

As usual, he is right: Musk isn’t going to get the likes of me into an electric Ford Lightning F-150 or even a Tesla. What Musk is looking for is to eliminate regulators and competitors so Tesla can go back to holding 80% of the market while investing less than 25% of free cash into capital expenditure. It’s fine with him if that market is limited to the top 20% of the income distribution. His concern is Tesla’s stock price, to which his enormous compensation is tied.

My students and I have been reflecting on these topics together. Some are giddy with winning bets on Tesla, crypto, and the election. But one giant bear of a 21-year-old was careful with his allegiance. When we discussed Musk, he quietly revealed that a young woman he had grown up with in his small town in New Hampshire had died in a fiery Tesla crash, “He’s in it for himself, not for us.”

MARIE CHRISTINE DUGGAN holds a Ph.D. in economics and is professor of business management at Keene State College in New Hampshire.

Sources: Chuck Squatriglia, “Feds Lend Tesla $465 Million to Build Model S,” Wired, June 23, 2009 (wired.com); Theodore Schleifer and Maggie Haberman, “Elon Musk Backed Trump With Over $250 Million, Fueling the Unusual ‘RBG PAC,’” New York Times, December 5, 2024 (nytimes); Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (Thrifty Books, 2009); Wall Street Journal, “Video: The Hidden Autopilot Data That Reveals Why Teslas Crash,” July 29, 2024 (wsj.com); Jarrett Renshaw, Rachael Levy and Chris Kirkham, “Exclusive: Trump team wants to scrap car crash reporting rule that Tesla opposes,” Reuters, December 17, 2024 (reuters.com); Mariana Mazzucato, The Entrepreneurial State (Anthem Press, 2013); Mariana Mazzucato, “Opinion: We socialize bailouts. We should socialize successes, too,” UCL News, July 2, 2020 (ucl.ac.uk); Josh Bivens, “The Inflation Reduction Act finally gave the U.S. a real climate change policy,” Economic Policy Institute, August 14, 2023 (epi.org);Alliance for Automotive Innovation, “(First Quarter 2024) Get Connected Electric Vehicle Quarterly Report,” July 2, 2024 (autosinnovate.org); Linette Lopez, “Make America Tesla Again,” Business Insider, July 28, 2024 (businessinsider.com); Linette Lopez, “Elon Musk Started a Price War that Tesla Can’t Win,” Business Insider, November 12, 2023 (businessinsider.com); Nicole Kagan, “How Elon Musk and His Trolls Attacked a Duke Professor on Twitter” The 9th Street Journal, April 15, 2022 (9thstreetjournal.org); Ben Glickman, “Ford Motor to Pause F-150 Lightning Production for Several Weeks,” Wall Street Journal, October 31, 2024 (wsj.com); Scott Evans, “The Ford F-150 Lightning Is the 2023 MotorTrend Truck of the Year,” MotorTrend, December 13, 2022 (motortrend.com); Plug In America, “2022 EV Tax Credits from Inflation Reduction Act” (pluginamerica.org); Lindsay Moore, “Will Newly Passed CHIPS Act Help Maintain Momentum for EVs?,” GovTech AI Weekly, August 10, 2022 (govtech.com); U.S. Department of Energy, “Alternative Fuels Data Center” (afdc.energy.gov); Maggie Christianson, “Tracking Electric Vehicle Investments in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and Inflation Reduction Act,”Environmental and Energy Study Institute, October 30, 2023 (eesi.org); Rafaele Huang, “Tesla is Losing Ground Against Its Biggest Rival in China” Wall Street Journal, February 10, 2025 (wsj.com); Peter Johnson “BYD Launches Sleek Song L electric SUV starting at $27,000 as Tesla Model Y Rival,” Electrek, December 15, 2023 (electrek.co); Camila Domonoske, “5 takeaways from Biden’s tariff hikes on Chinese electric vehicles,” NPR, May 14, 2024 (npr.org); Joseph Parrilla and Glencora Haskins, “The Bidenomics Investment Boom in Red America,” Brookings Institution, December 11, 2024 (brookings.edu); Eric Harwit, “Tesla Goes to China,” Analysis from the East-West Center, April 2022 (eastwestcenter.org); Anuska Dixit, “How China’s BYD Surpassed Tesla with Production and Battery Tech – reshaping the global EV market” Automotive Manufacturing Solutions, February 25, 2025 (automotivemanufacturingsolutions.com); Tim Higgins, “The Withering Dream of a Cheap American Electric Car,” Wall Street Journal, November 16, 2024 (wsj.com); Blane Erwin, “What is a ZEV Credit and how does Tesla make money with them?,” Current Automotive, July 31, 2020 (currentautomotive.com); Andrew Lee, “Blade Batteries: A Deep Dive into Performance and Safety,” Medium, Januart 26, 2024 (medium.com); Jörg Luyken, “‘High Frequency’ of Injuries at German Tesla factory included burns and amputation,” The Telegraph, September 28, 2023 (telegraph.co.uk); Anjeanette Damon, “Worker injuries, 911 calls, housing crisis: Recruiting Tesla exacts a price” USA Today, November 12, 2019 (usatoday.com); Sergei Klebnikov, “Here’s Why Elon Musk Was Really the Highest-Paid CEO In 2020,” Forbes, May 6, 2021 (forbes.com); Tesla Motors, Inc., “Tesla Motors Sets New Pricing for Award-Winning Model S,” November 29, 2012 (ir.tesla.com); Damon Lavrinc, “Tesla Pays Off All $465M in Federal Loans 9 Years Early,” Wired, May 22, 2013 (wired.com); Lora Kolodny, “Fatal Tesla collision with firetruck under federal investigation,” CNBC, March 8, 2023 (cnbc.com); U.S. Department of Transportation National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, “Investigation EA 22-002, Tesla Inc., 2014-2022,” June 8, 2022 (nhtsa.gov); International Energy Agency, “Infrastructure and Jobs act: Nationwide network of EV chargers,” July 10, 2024 (iea.org); Sandrine Levasseur, “A two-year assessment of the IRA’s subsidies to the electric vehicles in the US: Uptake and assembly plants for batteries and EVs,” Asia and the Global Economy, June 2025; McKinsey & Company, “The CHIPS and Science Act: Here’s what’s in it,” October 4, 2022 (mckinsey.com); U.S. Energy Information Administration, “U.S. share of electric and hybrid vehicle sales increased in the second quarter of 2024,” August 26, 2024 (eia.gov); M. L. Cummings and B. Bauchwitz, “Identifying Research Gaps through Self-Driving Car Data Analysis,” in IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles, December 4, 2024 (ieeexplore.ieee.org).