Discredited, Discarded, and Demented: Donald Trump and His Tariffs

Instead of using the Supreme Court’s decision as an opportunity to liberate himself from his biggest policy blunder, Trump has doubled down on tariffs.

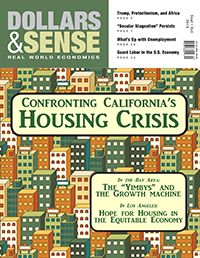

Third in a series, "A Sustainable Economy Rises in Los Angeles."

Wind chimes jingle in the warm L.A. breeze. Books to share are stacked in the entryway. Mosaic art abounds amid the garden's sunflowers and wrought-iron decor with the informality of a family home. But these multi-dwelling structures are in the heart of Koreatown, Los Angeles' most densely populated neighborhood, and are part of a cooperative of affordably priced homes and rentals that serve more than 70 residents and a dozen businesses.

This is a far cry from the infamous speculative real-estate market of Southern California. The land is owned by the Beverly Vermont Community Land Trust, a venture that offers an intentional community and resident control in L.A.'s exclusive, expensive, and volatile local housing market. The land trust and cooperative, components of the Los Angeles Eco-Village (LAEV), were cofounded by activist Lois Arkin in 1993, who envisioned a community of cooperative living and permanently affordable housing. Arkin's remarkable tenacity and commitment led to the creation of an urban village that continues to grow. Artists, electricians, tech workers, therapists, activists, and teachers find reasonably priced housing and commercial space in these four buildings. Because the housing is affordable, residents can participate in the arts, activism, and family life, and they can have a sense of safety and housing security in spite of instability and inequity in the local economy. The Los Angeles Eco-Village fosters the sort of diverse population that makes L.A. a vibrant and creative hub.

Developments such as the Eco-Village are not the norm, yet the need for them is undeniable. Unaffordability has created a dire housing shortage in a region where more than 20% of the population lives below the poverty line. The housing crisis is most visible in the homeless population living in Los Angeles County, but less visibly it also exacerbates poverty and the associated injustices for those with uncertain housing. Housing instability engenders job precarity, evictions, and negative health effects. Housing fragility disproportionately affects historically marginalized populations, the elderly, disabled people, and veterans. Long-standing racist policies and restrictive covenants have carved deep geographic pockets of poverty and housing inequity. The situation was made worse in the wake of the 2008 financial crash, when foreclosures of single-family homes created a fertile landscape for international real-estate investors and a predatory rental market. The result was skyrocketing rents, substandard conditions, and heartbreaking rates of eviction. Gentrification of older neighborhoods has forced displacement across race and income lines. There are simply not enough humane options. More than 50,000 people are reported to be living with homelessness on any day in Los Angeles County, and many more live on the precipice, residing in overcrowded and unsafe units.

The entire Southern California region has become the site of a dramatic housing struggle. More than 620,000 City of Los Angeles apartments are rent stabilized, but the policy includes state-mandated vacancy de-control, so every vacancy allows the apartments to rise to market rate, moving those units out of a reasonable price range. Wages have not increased significantly, while rental rates, the purchase price of homes, and the cost of living consistently rise. Many of the city's poorest people are severely rent-burdened, paying between 50% and 90% of their incomes toward rent. In this environment, home ownership is out of the question, with the median price of a single-family home in Los Angeles at $520,000 in April 2018, in a county where the median annual income was $64,300 in 2017. Six Southern California counties have seen similar increases of between 4% and 10% in housing prices this year, as well as a spate of foreclosed homes turned into corporate-controlled rentals. In recent years, financial conglomerates such as the New York-based Blackstone Group have spent over $10 billion to acquire single-family homes and create a rental empire, as the largest landlord in the United States. Nationally, more than 200,000 families live in single-family rental homes with non-local ownership, including more than 15,000 in California.

The city and county of Los Angeles have new public funding sources for numerous housing projects in development, but they won't come close to reaching the county's projected need of more than 550,000 new affordable rental units. The obstacles to producing these units are many: the often- burdensome red tape involved in new construction, complicated funding streams, a scarcity of building sites. But new development along with serious efforts to preserve existing affordable housing stock are necessary to deliver more stability to Angelenos. Policies such as mixed-income requirements and density bonuses for developers as well as encouraging "accessory dwelling units" (self-contained housing units on formerly one-family lots) can also help alleviate the shortage. Nationwide, philanthropic and affordable housing funders are trying to offset proposed cuts to federal programs with infusions of capital and program resources. While the housing affordability and availability scenario might seem grim, multiple innovative approaches to housing are gaining a foothold, becoming more viable and visible.

Into this stew of public and private efforts, the collective self-determination of a humble project like the Los Angeles Eco-Village offers hope. The growing movement for an equitable economy has a vision for cities that securely house everyone; a vision where the community has a voice in determining the rules of ownership, land use, living conditions, affordability, and permanent accessibility. A city and region that prides itself on innovation, progressive thinking, recognizing pioneers, and welcoming newcomers should also provide a place for artists, activists, and every-day residents involved in expanding the civic imagination. There are several examples of sustainable and just alternative housing solutions in progress. First, a growing number of community-owned land trusts and resident control projects are emerging, often as partnerships between land trusts and cooperative structures. Second, joint efforts to retain local ownership of the existing affordable housing stock are underway--ownership that increases the commitment to quality housing, abates rent- gouging, and deters absentee landlords. Finally, Los Angeles has a path to homeownership where first-time buyers can secure housing and build a modicum of wealth.

A community land trust (CLT) is a nonprofit whose members make land-use decisions that prioritize community interests in affordability and historic-resident protection. There are several currently operating around southern California, from Santa Ana to East L.A. In the neighborhoods of South Los Angeles, home to approximately 785,000 people (20% of L.A.'s population), housing is scarce, numerous buildings are unused or under-utilized, and the market is ripe for speculation. The TRUST South LA CLT, in partnership with nonprofit affordable housing developer Abode Communities, is working on several permanently affordable housing projects to deal with these conditions. The Slauson and Wall project, presently in the design phase, will house 120 families and includes a four-acre park and community center. The Rolland Curtis Gardens housing project currently under construction preserved 48 units of affordable rental housing, and added another 90, while guaranteeing first right of return to the original 48 families. The new TRUST Community Mosaic project is a collaboration to acquire and rehab small local occupied properties, with ownership by the CLT combined with limited equity housing agreements and training for the residents.

The democratic membership of TRUST South LA, composed of community members of all ages and backgrounds, believes passionately in creating long-term, intergenerational housing units. And they know that to thrive, national housing policy must embrace the land trust model. The members have supported and developed this organization through difficult economic times, unpredictable land markets, and political transitions. Many former volunteers are now in paid staff positions at TRUST South LA, and their primary focus is finding strategies to raise money for local land trust projects. As Executive Director Josefina Aguilar says, they can see immediate community improvements from the work they have done, but their goal is to expand the movement with federal, regional, county, and city sponsorship. "We want to elevate the conversation," says Aguilar, "to influence policy." The East LA Community Corporation (ELACC), a respected housing nonprofit, has another CLT project underway in Boyle Heights, a neighborhood facing deep conflict over encroaching gentrification. ELACC's CLT work will focus on developing programs for shared equity between occupants and program sponsors as well as a rent-to-own option, building new units with innovative designs that offer common living spaces, and educating community members about shared ownership and stewardship. ELACC leaders have found the city and county open to the development of CLTs, but the legal complexities of land transfers will require further active assistance to ease implementation. To build public-sector traction for land trusts, it is important that all parties acknowledge this changing social and economic landscape.

In the eastside neighborhood of El Sereno, a collaborative group is creating a CLT of land and multiple residential and commercial units in hopes of creating an autonomous development that moves toward "a moral economy," as cofounder Roberto Flores says. Inspired by the Zapatista movement of Chiapas, Mexico, they approach their work with a democratic, bottom-up philosophy, whereby they can construct safe and dignified living and working conditions without relying on an inconsistent political landscape.

The Los Angeles Eco-Village mentioned in the introduction also features a cooperative land trust model that serves as an example of successful property use alternatives. The land trust arm of the LAEV owns the land under 45 affordable units in the Urban Soil-Tierra Urbana Limited Equity Housing Cooperative, and an adjacent four-unit building with garages. A new quarter-acre acquisition next door is slated for an affordable and environmentally sensitive commercial space, a caf?, a hostel, and a community center. To make this community a success, Lois Arkin and the resident members have tackled financial limitations, embraced the work of building environmental awareness and shared culture, and undertaken the messy but gratifying work of bringing people together. Living at the LAEV has afforded long-time resident Joe Linton the freedom to become a well-known leader in transit and housing advocacy. He also has time to pursue his artistic endeavors, to share in the raising of his daughter, and, as he says, "To do what I believe in," to make "L.A. a better place ... because I did not have to draw down a big salary to live here."

Many of these CLTs offer shared equity, where home price appreciation is shared between the homebuyer and the program's sponsor--which could be an affordable-housing developer, a land trust, a public-sector agency, a community development financial institution, or a community investment entity. There is reduced risk associated with shared equity, and many CLTs have a standard practice of offering fixed mortgages, homebuyer education, and ongoing stewardship assistance. Shared equity properties also have significantly lower delinquency and foreclosure rates, while resale restrictions preserve the homes in affordability over time. A 2017 study by the Urban Institute showed that shared equity purchasers with incomes well below the area median had smaller mortgages and lower monthly payments than other purchasers. Shared equity homeownership makes low-income communities less vulnerable to the ups and downs of the market, allowing for greater job security and the ability to set aside funds for long-term savings, investment in retirement accounts, or education. And, as pointed out by Emily Thaden in Shelterforce this year, shared equity communities "advance integration by ensuring that affordable homes remain in neighborhoods that are experiencing gentrification or that are rich in community assets."

There are more than a thousand resident- controlled cooperative housing units in Southern California with shared or limited equity arrangements, including many formed through the Low-Income Housing Preservation and Resident Homeownership Act of 1990. These units are difficult to find; their waiting lists are full and there is an understandable lack of turnover. Recent statewide legislation has lightened the legal and tax burdens on cooperative and shared-ownership endeavors, but Californians could unify and strengthen their approach to encouraging public support for these efforts. While government officials, housing activists, and philanthropists struggle with displacement and the injustice of gentrification and market forces, well-intentioned investors who can handle a long-term return-on-investment schedule can also advance shared-equity initiatives by bringing both capital and new strategies.

More joint efforts are underway to retain local ownership of the existing affordable housing stock, or what housing policy experts call "naturally occurring affordable housing" (NOAH). These units are often at risk of being demolished and rebuilt as market-rate homes, but organizations such as TRUST South LA and ELACC, in partnership with local and national housing funders Enterprise and Genesis LA, have seen success in preservation projects with low-income residency requirements. Initiatives that involve local government and multiple partners require a tenacious set of community members, strategic organizations, and passionate government officials who can work effectively from the inside, and a sizable dose of political will to leverage against powerful for-profit interests.

Earlier this year, L.A. housing officials, the mayor, and city council created an innovative initiative through the Los Angeles Housing + Community Investment Department called the NOAH Loan Program, which allocates $2,000,000 to these sorts of efforts (largely from an affordable housing trust fund). This program will provide the funding to acquire, improve, and retain occupied low- and moderate-income multi-family properties to organizations with track records in affordable housing. Local ownership of these properties is critical to keeping a supply of existing affordable rentals available and keeping historic residents in their homes. This pilot program will engage the city housing agency, local affordable housing organizations, CalHFA (the California Housing Finance Agency, a self-supporting state agency that serves as a partner in many municipal programs), and the New Generation Fund to protect rental buildings from the vagaries of speculation. They are launching with a 50-unit building in East Hollywood.

The City of Los Angeles' Low Income Purchase Assistance (LIPA) program for first-time buyers will help individuals and families who qualify as low income to buy their first homes by providing a loan of up to $60,000 for a down payment, closing fees, and acquisition, thereby reducing a buyer's mortgage burden. Qualified homebuyers can also receive a mortgage tax credit, further building the strength of their income and making costs more manageable. In the last three years, the city has enabled more than 300 purchases by connecting potential homebuyers with long-term loans from vetted small-scale mortgage lenders at low-to-average interest rates--and in return, the city receives a percentage of the net appreciation of the property at sale (based upon the amount of the city loan divided by the purchase price of the home). The program also has a strong funding foundation and homebuyer education offered through community-based organizations, but the primary challenge it faces is finding homes priced below $500,000 that are in respectable condition. The market keeps that stock of inventory scarce, and cash offers, often from corporate investors, compete for the same properties. (A similar program for moderate-income homebuyers is on hiatus until the funds are secured later this year.) CalHFA also provides primary mortgage loans and down payment assistance to first-time homebuyers, including special programs offered to public school teachers, administrators, school district employees, and staff.

Shared equity, land trusts, cooperativism, and first-time homebuyer help are part of a recent wave of efforts to deal with the housing crisis in Los Angeles. They are not sufficient reparations for housing apartheid, economic oppression, and displacement. They are, however, a small but growing means for building collective power, as part of the bigger project of equity and housing justice. This is not a decisive list; new ideas emerge regularly, including moratoriums on predatory purchase deals, and models of patient, nonprofit, mission-driven investment in existing buildings. There is a real and bitter distance between the reality of tens of thousands of people living with homelessness or at serious risk of losing housing in L.A., and the picture of what is possible in the immediate future--community ownership, resident decision-making, safe homes, and intergenerational affordability. But these projects show that we can choose solidarity over hardship. People are speaking up to affirm their right to housing and to imagine well-being for the community as a whole. They proclaim that we can work and live together. The power of the members of TRUST South LA, the tenacity of Lois Arkin and the LAEV community, the vision of ELACC, the political will that Angelenos are building, the self-determination that many fervently hope for--together, these can bridge economic divides in the City of Angels, renewing the region's dignity, solidarity, and livability.