Health Insurance for 20 Million is at Risk

If Congress fails to renew the ACA enhanced benefits, millions will be unable to access the health care they need.

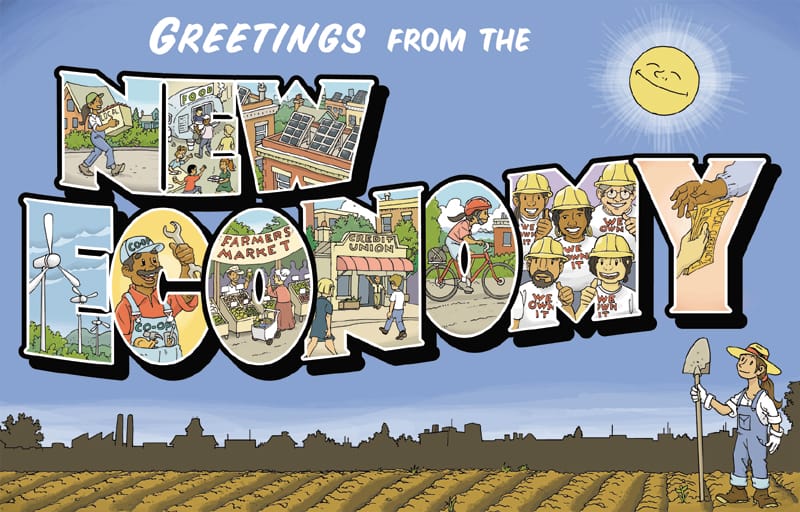

In a race against climate change, a new movement seeks to build a just, sustainable world.

"Are you ready for a new economy? Are you ready for a new politics?" The challenge at the podium came from Gus Speth, the courtly co-founder of the Natural Resources Defense Council, now a professor at Vermont Law School, who is on the board of the newly created New Economics Institute (NEI). The occasion was the founding conference of NEI, held at Bard College in early June, and Speth was making a call for "an economy whose very purpose is not to grow profit?but sustain people and the planet."

NEI is the remade E.F. Schumacher Society, the group based in Massachusetts' Berkshire mountains that promoted the wisdom of the author of Small Is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered for over 30 years. In honor of this early champion of a sustainable, just economy and the idea that big is not necessarily better, the Society nurtured economic innovations that support community building--community supported agriculture, local currencies, local land trusts.

With the help of the London-based New Economics Foundation, the Schumacher Society rethought what kind of "think and do" tank is needed to transform our fossil fuel-powered, finance-bloated, inegalitarian economy into one that is resilient, just, and sustainable in the environmental and economic transition given true urgency by climate change. And with the help of some deep pockets, it re-launched as NEI and pulled together, all in one place on Bard's rural campus on the Hudson, some of the thinkers and organizers who might have a piece of the puzzle.

People reimagining ownership and work on the job or in the academy, ex-Wall Streeters revealing the secrets of how to curb the power of big finance, community people reclaiming the commons--taking air, water, and land out of the market--and rebuilding local economies from the bottom up, advocates struggling with government to make it responsive, and social scientists who are remaking our economic indicators--they may never have talked with one another before the Strategies for a New Economy conference. But as Bob Massie, the new executive director of NEI said, together they created "raw energy."

The "New Economy" moniker is bubbling around lately, with a meaning recast far from President Bill Clinton's neoliberal usage 20 years ago. The venerable Washington DC-based Institute for Policy Studies has its New Economy Working Group, a partnership with Yes! magazine and the 22,000-member Business Alliance for Local Living Economies (BALLE). At the core of the call for a New Economy is an effort to come up with practical alternatives that democratize the control of the economy--including workplaces, finance, and the structure of the firm--in ways that are ecologically sustainable.

The focus on finance--on shrinking a dangerously unstable, extractive banking sector and nurturing an alternative one--is powered by such people as John Fullerton, the former JPMorgan managing director who launched Capital Institute to promote the idea of finance "not as master but as servant" and sees a role for "social impact" investing in the New Economy.

It is in the New Economy movement that you'll hear people talk about how to build a "no-growth" economy that shares more and taxes the earth less, a view promoted in the United States most notably by Boston College professor Juliet Schor. On the board of the new NEI are thinkers like Peter Victor of York University in Toronto, author of 2008's Managing Without Growth: Smaller by Design Not Disaster, and Stewart Wallis, head of London's New Economics Foundation, which has been popularizing the no-growth idea for years.

"Even if everybody was to rediscover Keynes, that's not the answer," Wallis told the NEI crowd, referring to the British economist who popularized government investment in the economy during downturns, even if it means running deficits, in order to boost demand and employment. "We can have an economy with high well-being, high social justice" that destroys the planet. "We need a new model, an economy that runs on very different metrics, maximizing returns to scarce ecological resources, maximizing returns [to] human well-being, good jobs."

"We have to move from talking about ourselves as consumers to [regarding ourselves as] stewards." But the New Economy movement is a big tent, and for some growth isn't the question. For Marjorie Kelly, author of Owning Our Future: The Emerging Ownership Revolution, and a fellow of the Tellus Institute, the Boston-based think tank focused on sustainability, growth isn't the focus. In a chat at the conference "bookstore," she said,

The problem is not growth but too much finance. You have the overlap of debt, unemployment, lack of jobs for youth. ... We can't have capital markets run the economy. It has a destructive focus. It's starting to fall apart. That's terrifying. You hold on desperately to what you have as it collapses. But no, you have an alternative. You have the Right, cutting taxes, deregulating. No serious thinker believes that those are the solutions. ...There's an inevitable sorting process. There's some loony ideas and we haven't sorted that out yet. But they said that about democracy.

Following the NEF and Schumacher, the New Economy umbrella also covers those promoting more realistic economic indicators that measure people's well-being and ecological costs, including the Green GDP. It considers which business forms--not just worker-owned companies but also so-called B-Corporations that consider social impact--might be compatible with a just, sustainable economy. It covers those challenging the decontextualized, value-free world of neoclassical economics because, as Massie said, "our current theories have blinded us." In late June, this was the agenda of Juliet Schor's week-long Summer Institute in New Economics at Boston College, where graduate students sat at the feet of Gar Alperovitz of the University of Maryland, James Boyce of the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, Duncan Foley of the New School, and others.

It's a big tent, and feels a bit like the Progressive Movement of the early 20th century, when many elites and middle-class people began questioning and even challenging how capitalism was organized. Partly because of its high price tag, the Bard gathering was almost entirely white and highly educated, deploring poverty but not necessarily touched by it, yet highly motivated to build a more communal, cooperative economy. How these middle-class reformers will share leadership with low-income immigrants, progressive unions, and co-ops--key social bases for the movement--is a bit of a mystery. It's no mystery, however, that any massive change in the U.S. political economy needs all these sectors pulling toward change.

Andrew Simms, the Brit known for his creative leadership in The Other Economic Summits (which dogged G-7 meetings for years before turning into London's New Economy Foundation), put class and political power on the table when he told the meeting, "When I hear people talk about sustainable capitalism, they are making a strategic error," adding "If we could get where we need to be by writing reports, we would have gotten there." The knowledge that the activists need to raise their game ran through the conference. In his plenary, Massie acknowledged who largely was not represented in the room: unions, communities of color, youth, business. He asked his audience to ask in turn, "How can we work together? How can we make this bigger and make the New Economy a reality?"

It was only April 2009, at University of Massachusetts-Amherst, that the U.S. Solidarity Economy Network held its own sizeable gathering. That brought together people in progressive unions, worker co-ops, credit unions, food co-ops, green jobs initiatives, and even the peace movement. Inspired by the U.S. Social Forum in Atlanta in 2007 and Solidarity Economy movements in Latin America and Quebec, the network was soon celebrating the United Steel Workers' announcement that it would try to take over smaller enterprises for worker ownership, based on the example of Spain's Mondrag?n cooperatives--an effort slowed by the impact of the economic crisis on the union. Canadian unions reported using their pension funds to support worker ownership.

There is some overlap between the Solidarity Economy and New Economy networks. The NEI conference sought out sustainable business networks and social venture funders while the solidarity framework inspired more lower-income people and people of color. Worker co-ops came to the New Economy gathering at Bard. The green Cleveland co-ops--the complex including industrial laundry and urban farm (see "America Beyond Capitalism," D&S, November/December 2011)--received a rousing reception. And NEI board member and plenary speaker Gar Alperovitz is one of worker ownership's most vocal academic champions. But as Donnie Maclurcan, of Australia's Post-Growth Institute asked me at the opening session: "Where is the acknowledgment of the custodians? [Thanking the janitors] is standard in Australia." A participant set up a sign on a picnic table during lunch asking people to come over and talk about race and class. The divide is deep. Speth was another who took on the divisions in the movements directly but warned the group they had to overcome it:

Critical here is a common progressive platform. It should embrace a profound commitment to social justice, job creation, and environmental protection; a sustained challenge to consumerism and commercialism and the lifestyles they offer; a healthy skepticism of growth mania and a democratic redefinition of what society should be striving to grow; a challenge to corporate dominance and a redefinition of the corporation, its goals and its management and ownership; a commitment to an array of prodemocracy reforms in campaign finance, elections, the regulation of lobbying; and much more. A common agenda would also include an ambitious set of new national indicators beyond GDP to inform us of the true quality of life in America.

Thinkers like Alperovitz support democratizing our economy by building out our existing network of land trusts, consumer and worker cooperatives, employee stock ownership programs with workers participating in governance, and credit unions--building off institutions crisscrossing the country. He mourns the age of unions as past, noting that more workers are in worker co-ops or ESOPs than private-sector unions. He sees these cooperative endeavors as providing a key base for building the future. He gives a political blueprint calling for redirecting federal, state and local government support toward these enterprises from corporations. This echoes the "cooperative commonwealth" envisioned by some 19th-century populists, and has healthy if long-lost roots in American thought. Markets are left intact but so is government action for the common good.

With a much greater ecological consciousness than many of her peers, Juliet Schor (like Costas Panayotakis in his new book Remaking Scarcity) calls for a struggle over our subjectivity and how we define our needs in building a more egalitarian, sustainable economy. While Schor was unable to attend the conference, in some ways she captures the downshifting philosophy of much of the audience better than keynoter Alperovitz. She warns us that capitalism's ability to nimbly create new needs and intensify consumerism needs to be challenged on an ecological and moral basis. Can we remake the common-sense values that are lodged at the core of our current system?

Schor lays out the more explicit vision of what almost seems like a social crusade, yet relies on individual action. She argues we need to remove ourselves from the market, step by step where we can: by working part-time, making do with less disposable cash income, and doing more on our own... That means everything from cooking to making clothes to home construction. Drawing on the alternative economy movements promoted by the old Schumacher Society, Schor champions local time dollar schemes, freecycle sharing, and barter. These schemes seek to intensify community values by intensifying your web of support with your neighbors. Ultralocal, home-based solar energy production should spread. People should embrace the slow money movement by investing locally through credit unions other other local networks, not through big finance. Meanwhile, she supports expanding the welfare state so that we are not subject to markets when it comes to our health, to expand living-wage jobs and in protecting the commons.

While the thinkers and policy heads dominated the panels at Bard, in the hallways I met an organic farmer who is a soil activist and writer, a big-city organizer trying to launch a Cleveland-style worker-owned initiative in an impoverished area, an Occupier, a member of a worker coop, and a Rhode Island man hoping to launch a community currency so that impoverished residents can find value in their skills. I also met Frank Nuessle of the Public Banking Institute, which is championing state banks modeled on North Dakota's, and Sean McGuire, Maryland's director of sustainability who championed the Genuine Progress Indicator so the state now measures economic growth with an eye to its social and ecological costs. Attending in force were Transition Woodstock members. These last are part of the international Transition movement begun in the U.K. that tries to encourage communities to downshift and take up resilient, ecologically sound practices so that we respond to climate change in an egalitarian way. NEI's London partner, New Economy Foundation, actively supports the Transition movement.

One of my deepest conversations was with Bonnie Rukin, regional coordinator of Slow Money Maine, which holds events matching people who can give loans or grants to enterprises creating a local sustainable food system. That might mean an organic member-owned restaurant or seaweed harvesters. Inspired by Woody Tasch, the former venture capitalist who founded Slow Money, the Maine group is one of the more successful regional spinoffs. Other people at the conference reported struggling projects in Ohio and Colorado. "A funder meets a farmer. A farmer meets a legislator. We have a lot of networking time at our meetings," said Rukin, a 62-year-old former organic farmer with a nonprofit background. "We catalyzed the flow of $3 million ? and untold amounts of awareness. In terms of hunger needs, we're second in the country. We're on par with Alabama. We want to develop the social fabric."

"We started with 30 people gathering and we're up to 450 people," said Rukin. "They're each given 10 to 15 minutes to tell what they did?then the bell would ring," said Jonathan Lee, a Belfast, Maine Slow Money activist. He describes the scene: "People in the audience are from foundations, government?" Some skilled businesspeople offer their time.

Jonah Fertig, a member of the Sprouts cooperative restaurant funded through Slow Money Maine, said simply, "It's helped us to connect to different resources and people," including fellow "farmers, cooks, food procecessors?"

Less explicitly anti-capitalist than many of the alternative economy folks are some of the business-oriented elements of the New Economy movement that wrestle to reform traditional market-based tools so they create incentives toward sustainable, socially just practices. Or sometimes they just try to create a counterforce to the big-business lobby. "Policies that provide social benefit are called bad for business," David Levine, founding director of the American Sustainable Business Association reported to the Bard gathering. "It was time to ask, ?Bad for whose business?'"

The ASBA formed after the election of President Obama to provide lobbying muscle and build political power for policies that tackle global warming and invest in job growth. "That means showing up before the Energy and Commerce committee and say why regulations are very important for business." It now networks 150 existing local and specialized business associations representing 150,000 members. The New Mexico Green Chamber of Commerce and women's business associations are among their members.

"We can actually produce chemicals that are not toxic. We can produce materials that are recyclable," said Levine. "What are we up against? It's the $200 million budget of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. While we might not have the money, we can show up and have a voice."

Being obsessed with profit and growth comes with costs that don't show up in the numbers. Community stakeholders and goals are ignored in corporate ratings, and companies are captive to Wall Street's short-termism. And Wall Street's goals are written into corporate law. A former bond trader came up with a new corporate form, B-corporations, that allows companies to be evaluated by their social performance, not just their economic bottom line. Since 2010, laws allowing B-corps have been enacted in eight states, most recently in Louisiana. Nathan Gilbert's job at B-Lab, a New York-based nonprofit, is to make it spread.

Strategists who think investors will voluntarily make better decisions if they knew the true impact of companies are also creating alternatives like GIIRS, the Global Impact Investing Rating System, to reveal what businesses are doing for the environment, job creation, and job quality.

But only 500 companies are chartered as B-corporations, mostly small firms. "They have $3 billion total capitalization--that's cappuccino money at Apple," said Allen K. White, vice president of Tellus, another speaker. Still, he said, "Ownership does matter. It has a moral and operational quality."

Meanwhile, he pointed out, most of the world's economic activity is controlled by the 1,000 largest corporations, untouched by many of these ideas and local movements. Richard Branson of Virgin may have told Davos, the gathering of the high and mighty, that we are seeing "the end of capitalism," as White noted. And indeed the Solidarity Economy and New Economy movements are debating what should replace it.

The stakes are high. The environmental writer and campaigner Bill McKibben was on hand to give the conference a sense of urgency to curb corporations' destructive power before the imminent damage caused by climate change is irreversible. "It is a fundamentally altered planet," he told a packed auditorium. Given our interconnection, it's not enough to work in our home communities. "If we don't take care of this large global crisis, we won't realize the future toward which we are all working.

"This is not only a huge practical dilemma but a moral one too," he said, reporting on the dengue fever epidemic he just faced in Bangladesh which he survived when undernourished people died. "Today we learned this spring was the worst spring and the most extreme. Saudi Arabia had the hottest rainstorm recorded on this planet--109 degrees. We're building a science fiction story and I don't know if we can stop it."

"Here's the good news: Most of what we need to do to deal with global warming will also help [people]," he said. With those marching orders, his middle-class reform army filed out.