Fighting Climate Change in Portlandia

Not only is failure not an option, those fighting to avert cataclysmic climate change have achieved important successes worthy of celebrating.

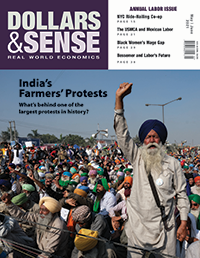

In November 2020, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, landowning farmers, and mostly landless farmworkers--men and women, young and old--gathered outside the capital city of New Delhi for one of the biggest demonstrations in the world. The assembly of yellow and green scarves, turbans, and flags was met with water cannons, barricades, and a lathi- (baton-)wielding police force that prevented them from entering the city. They were, however, joined by industrial workers, students, and civil rights groups protesting regressive and authoritarian policies. There were more than 200 million protesters opposing the government's economic policies. The farmers have continued their protests. On January 26, 2021, the 74th anniversary of India's Republic Day, the ranks of protesters swelled as they were joined by more farmers and farmworkers, along with their tractor-trailers (also referred to as "trollies"), and trucks as they marched and drove in a rally demanding their right to a livelihood and the right to protest, as enshrined in the Constitution.

The protests were a reaction to a set of farm bills that were proposed in June 2020 and passed on September 28, 2020. These bills were not afforded the treatment of a truly democratic process, which would have involved the input of state governments and the people most impacted by the proposed legislation.

Farmers in the state of Punjab had been protesting against the then-bills since June 2020 at the state level and when that failed, they decided to take the fight to New Delhi. The protesters were initially drawn in large numbers from the northern states of Punjab and Haryana, and later from the western part of the state of Uttar Pradesh (UP); all three states are in close proximity to New Delhi. As the days rolled by, they were joined by protesters from far-flung states and were also supported by solidarity rallies and marches in other states.

Tens of thousands of protesters first set up camp in the biting November cold and are now preparing for the unrelenting New Delhi heat. They have been successful in occupying five different locations and partially or fully blocking the major highways near these sites that run into the city. What started out as a temporary blockade has turned into a semi-permanent encampment. Some of the protesters have been in attendance with up to three generations of family members; others are on rotating shifts with family members, friends, and neighbors from their villages. The protesters have proclaimed that they have arrived with enough provisions for six months and are willing to stay for as long as needed. They perceive these farm laws as a matter of life and death. The protests, which are farmer-led but include a wide variety of groups, have come to represent a struggle against an economy that prioritizes profits over life. They demand an economy that represents the needs of the people--an economy that recenters agrarian livelihoods, food security, and human dignity at the core of economic policymaking.

The farmers' and farmworkers' unions that are protesting the recently passed federal legislation have critiqued the prior structure of agricultural markets, too. Before these new laws, government- regulated markets (mandis) were overseen by individual state governments. The intention was to license traders and middlemen and regulate their transactions with farmers. Most farmers in India have small landholdings, and the average farmland is less than 2.5 acres. Hence, state regulations were intended to reduce the risk of the exploitation of India's farmers by traders and middlemen. Instead, the license requirement created barriers to entry by limiting the number of traders and other intermediaries in the mandis. This inadvertently left farmers with little bargaining power and made them highly dependent on middlemen, who also played the role of financiers, information brokers, and traders. Farmers were often forced to accept lower prices as a result.

Farmers' unions have long called for changes to this flawed system. However, instead of leveling the playing field, the new farm laws appear to have been formulated specifically to benefit private corporations. While the federal government and media have portrayed the bills, and now laws, as benefiting the farmers, the changes that these laws usher in are far from the reforms that farmers' and farmworkers' unions demanded. They pave the way to displace middlemen and small traders without attending to the needs and long-held demands of farmers to create a more equitable system. The laws fulfill the federal government's mandate to create markets that are profitable for corporate players at the expense of the livelihood and food security of the country's citizens.

When it comes to these new laws, farmers and farmworkers have a range of concerns, from the erosion of government supports and food security to changes in how contract farming is carried out.

First, the issue of paramount concern--the trigger for the protest--is the minimum support price (MSP), which is a price floor that guarantees a minimum price for farm produce. This ensures that farmers are protected from some degree of price volatility in national and international markets and is a common policy measure in a number of countries, including the United States. The recent laws, however, do not clarify how the MSP, which acts as a price floor for 23 principal crops, will be impacted by the legislation. The government has made some assurances that the MSP will continue despite deregulation. However, farmers and farmworkers are concerned that under the new laws, the MSP is unenforceable since large private agribusinesses and corporate firms may refuse to purchase crops at the higher MSP rate.

While MSP has eroded in many states, it is still strong in the three states which have contributed the bulk of the protesters (Punjab, Haryana, and UP). Farmers and farmworkers from these states are worried that the farm laws would create two parallel markets: the government-run mandi with the requisite regulations and a "free" market. Private corporations may initially lure farmers away from mandis by offering prices greater than the MSP. If this starves the mandis of sellers and they are forced to close, it will mean that farmers can no longer count on a guaranteed price for their produce. It also means that private corporations can accumulate monopoly power over the supply chain, thus effectively giving them control of prices. Further, farmers are also apprehensive that the state may favor open markets over mandis in order to stock up on essential food grains for emergencies or for its food distribution program.

In sum, farmers are concerned that the relationship between the Indian state and farmers, wherein the state provides some degree of revenue guarantee, will change drastically. This revenue guarantee is particularly significant because agriculture is an increasingly unviable source of livelihood and yet the economy has not produced sufficient alternative employment opportunities. The Indian state did not help matters by foregoing a consultative process with farmers' and farmworkers' unions when crafting the new farm laws.

Second, protesters and their allies are fearful about the impact of the MSP on the Public Distribution System (PDS), which ensures the provisioning of a fixed quantity of staple foods for free or at government-regulated fixed prices for 75% of the rural population and 50% of the urban population, as mandated by the National Food Security Act of 2013. The Indian state acquires this food from mandis at the MSP rate. With the strengthening of corporate players, the concern is that farmers will be forced to sell at low prices to corporations who will then sell the produce at higher prices, which would increase the cost of government procurement. This would undermine the PDS system as a whole, thus affecting a large proportion of the Indian population that can't even afford to purchase food at current market prices.

Protesters are concerned that the farm laws will also further erode the minimal social protections afforded by the Indian state. Economic policies in the last two decades have reduced social benefits and investment in social infrastructure and have privatized profit-making public utilities to the detriment of workers and consumers. The pace of neoliberal policies has accelerated under the current ruling political party, BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party), which has been in power since 2014. A government committee, along with the Chief Economic Advisor to the federal government, Arvind Subramanian, recently called for direct cash transfers rather than the current "in-kind" delivery of staple foods, and a reduction in PDS coverage from the current 75-50% to 20-40% of the rural and urban population, respectively. These recommendations have been cited by protesters as evidence that the current government is interested in dismantling or weakening the PDS system, thus galvanizing rural farmworkers as well as urban industrial and service workers--those who would be most affected by changes in the PDS--to oppose the farm laws.

Farmers from all states are also worried about the provisions of The Empowerment and Protection Act, which specifies new rules on contract farming. While it ostensibly lays out the rules of the game for engaging in contract farming, there are no provisions to safeguard the interests of mostly small farmers against corporate interests with a higher degree of bargaining power. The monthly income for landholding farmers ranges from $7.80 (for marginal farmers with less than 2.5 acres of land) to $103 (for large farmers with more than five acres of land). (I used an exchange rate of U.S.$1 = Rs. 73. These low incomes are often supplemented with other livelihoods.) Farmers depend heavily on unpredictable monsoons that have become even more capricious on account of climate change, and they also lack access to adequate storage for crops.

While farmers are continuing to struggle to make ends meet, agribusiness startup investments in India's farm sector have increased significantly in the last couple of years. For example, in the first half of 2019, investments in such businesses totaled $248 million (a 300% increase from 2018) and have mostly been focused on improving the supply chain. These figures, however, do not account for the large corporate players desirous of expanding their presence in the farm sector in India. Farmers do not expect to benefit from these investments in the agricultural sector. On the contrary, by implementing the "one nation-one market" policy and infringing on individual states' ability to legislate on contract farming based on specific crops, regional economies, and geographies, protesters believe that the new farm laws codify an uneven playing field that's not in favor of farmers or farmworkers.

This perception is alarmingly reinforced by provisions in each of the new laws that explicitly prohibit legal challenges against the state or private corporations. This means that farmers cannot sue agribusiness players for any breach of contract. Small farmers typically do not have the financial wherewithal to engage in legal challenges, especially when it comes to challenging large entities. Nevertheless, these provisions, which are integral to these laws, reinforce the perception that the laws were meant to benefit private corporations and have far-reaching implications not just for the agricultural sector but for all denizens of the nation.

The changes wrought by these laws have been made against the backdrop of an acute agrarian crisis that has lasted for more than two decades. Since the mid-1990s, when India undertook economic liberalization, the agrarian crisis has resulted in more than 300,000 suicides by farmers and farmworkers, according to the National Crime Records Bureau. These have been primarily due to high levels of indebtedness and the inability of farmers to withstand market and natural shocks. Yet 42% of India's population of 1.3 billion continues to depend on agriculture, either as farmers or farmworkers. The other viable alternative is mostly low-wage informal employment that falls outside the ambit of government laws on minimum wage and workplace safety; more than 80% of those outside of the agrarian sector are informally employed. It is therefore unsurprising that India's ranking on the Global Hunger Index and the country's child nutrition levels are abysmally low. The benefits of high economic growth have been highly unequal; according to Oxfam, the top 1% of the country's population holds 77% of the nation's wealth. The pandemic has worsened inequality, as it has in other countries, like the United States. The wealth of India's billionaires increased by 35% during the pandemic, whereas 122 million people lost their jobs during the same period.

The federal government's imposition of the new farm laws during the pandemic reeks of its preoccupation with profits and markets--the laws are a grotesque attempt to concentrate power in the hands of big corporations. One of the demands of the farmers is to roll back the new laws and instead implement the recommendations of the National Commission on Farmers, which was formed in 2004 before the current political regime came to power. Under the direction of professor M.S. Swaminathan, who led India's Green Revolution, the Commission proposed structural changes that would address the decline in farm incomes and productivity, the high number of farmer and farmworker suicides, as well as indebtedness, access to credit, and landlessness. Unlike the recent laws, these recommendations would actually address the crisis that farmers and farmworkers are facing.

The farmer-led protests that began in November 2020 against the farm laws that would lower agrarian income and reduce food security are impressive, though their outcome is so far undetermined. Nevertheless, the protests have already garnered significant victories that are likely to reverberate throughout society and lead to political action.

First, the farmers' protests have not only forced the issue of monopolization and the increasing corporatization of agriculture into everyday conversation, but they have also extended the critique to neoliberal policies that have celebrated the monopolization and privatization of health care, education, and other public services.

Second, protesting farmers have also been joined by farmworkers, particularly from certain regions in the state of Punjab. This is surprising because of the conflictual class relationship between farmworkers and farmers. Farmers are landowners, even if they are small landholders, whereas farmworkers are mostly landless and are employed as daily or seasonal wage workers by farmers. Also, in the states that have contributed the most protesters, farmworkers tend to be Dalits, who are lowest in the caste hierarchy, whereas farmers typically belong to higher castes. Yet, some farmers' unions in Punjab have been working in conjunction with farmworkers' unions to improve wages, mitigate caste-related violence directed at landless Dalit farmworkers, and pressure the state for better living conditions. The farmers' unions hope that this will build a stronger coalition that demands better treatment for agrarian India. However, there are severe challenges to this class-caste unity against state and corporate interests. This alliance is, moreover, nonexistent or nascent in many regions. Yet, it represents a new mode of politics in India, which has typically been fractured along class-caste lines.

Third, women have taken on an incredibly important role in this struggle. This is especially notable because women in India have a very low status and are considered undesirable as shown by their low sex ratio at birth of 900 girls to 1,000 boys in 2015, as well as women's low labor force participation rate in both the formal and informal labor force, which was about 20% in 2020. Furthermore, women from North India, who are the majority of the protesters, typically experience lower mobility and hold few leadership positions or public roles. Yet, women from the state of North India have been prominently visible among those organizing the protests. Many women, including Dalit women, have travelled to New Delhi to represent their sons, husbands, and brothers who have committed suicide due to the agrarian crisis. Women have taken on the role of organizing daily rallies and cultural performances on social issues and even editing the Trolley Times, a bilingual (Hindi and Punjabi) newspaper that is produced by the protesters, for the protesters. They are demanding the right to financial security as farmers and farmworkers and asserting their right to occupy public space as "protesters in their own right," according to Navkiran Natt, the quiet but tenacious dentist-turned-co-editor of Trolley Times (which was named after the trolleys, or tractor-trailers, that have become a symbol of the farmer-led protests). They have also organized an International Women's Day celebration to recognize and honor the contributions of women as farmers, farmworkers, and as those responsible for sustaining households and families.

Fourth, farmers, farmworkers, and representatives of farmers' and farmworkers' unions have travelled from across India to the protest site in New Delhi. This cross-regional participation and solidarity is a historic moment in post-colonial India, which has maintained strong regional and subnational identities. More than 40 farmers' unions have come together under the banner of Samyukt Kisan Morcha (United Farmers' Front). Not only has this organization coordinated negotiations with the government as a collective entity, but it has also coordinated strategy and tactics, and issued media briefs, press conferences, and statements since November 2020. It is also in active discussion with more than 450 farmers' and farmworkers' unions across the country to coordinate actions in individual states for those who cannot travel long distances to the capital city during the ongoing pandemic. This is immensely significant because it represents a surge in solidarity between people who are subject to widely different economic and political histories while also subverting regional and subnational insularity.

Fifth, the protesters collectively model an alternative political vision. Tens of thousands of protesters have been camped along five highways leading to the capital city since November 2020, through one of the coldest winters the city has ever experienced. They sleep in trucks and tractor-trailers and makeshift tents. They eat collectively in langars (community kitchens that run on the principle of service, or seva, which is integral to the Sikh faith) run by local allies or the protesters themselves. Women are not necessarily relegated to kitchen work, and men are learning to cook for the langars in contravention of conventional gender norms. Protest sites have transformed into temporary mini townships with vendors and medical centers. There is a space for film screenings, and the social media accounts that have been set up by the protesters are deftly managed. More significantly, through the Trolley Times, protesters challenge the incorrect and negative portrayal of the struggle in the mainstream press and aim to keep all protesters (particularly the elderly, who form the bulk of the protesters and are not on social media) up to date on news across the five protest sites. The paper prints declarations made by the protest's leaders, engages in political education about the history of agrarian struggles in India, and provides space to issues of caste and gender that are typically ignored. They also have a very active Twitter account (@Kisanektamorcha) which allows them to reach youth, members of the Indian diaspora, and international allies with their messaging.

The historic farmer-led protests are a clear response to decades of neglect of the agrarian economy, which until a few decades ago was the backbone of the Indian economy and, as noted earlier, still employs 42% of the workforce. The moral and policy stance of the federal government has been that of a benevolent patriarch that needs to be firm and sometimes stern (including activating the police, military, and paramilitary forces as needed), to support the growth of the economy, which allegedly benefits its denizens. The solution to the agrarian crisis, which is in no small measure a result of neoliberal policies, is sought in the implementation of yet more neoliberal reforms. The federal government is unwilling to learn from the failures of the individual states that have implemented similar policies.

A generous interpretation would be that the government is na?ve, uninformed, or incompetent. A more realistic interpretation lies in the history of the state-market nexus that was strengthened since neoliberal reforms were first adopted in 1991 by the Congress Party. Since then, successive governments have attempted to mollify and woo Indian and multinational capital. None have been as strident in their efforts as the BJP. The current protests cement the identification of the BJP with corporate interests in the popular imagination.

The Indian state under both political parties--Congress and the BJP--has ignored or actively obscured lessons from the innumerous failures of neoliberal policies. Regular people finally appear to be waking up to the wretched conditions of their brothers and sisters who are toiling in the agrarian economy with little protection from the federal or state governments and who now find themselves pitted against corporate players. For example, recent revelations about the e-commerce giant Amazon's operations in India confirm what the protesting farmers have been saying all along, according to a recent post by the economist Rahul Varman at the Research Unit for Political Economy blog: "The Prime Minister and the Finance Minister have become the greatest cheerleaders for big capital," as the government looks the other way while Amazon evades regulations, or shapes policy to favor Amazon and other big corporations. According to Varman, the revelations about Amazon show that "the farmers are correct: recent policies and new laws will lead to their further marginalization and even decimation while corporates further consolidate their gains, with little actual oversight by the State."

The farm laws primarily serve the needs of profits and power. The farmers' protests constitute a challenge to such principles and offer a critique of the state and the economy. Even more importantly, in the course of protesting, farmers and farmworkers are developing and offering an alternative vision of the economy that prioritizes livelihood and food security for all; recognizes the deep divisions of caste, class, gender, religion, and regional differences; and makes an attempt to tackle them. The protests offer a vision of a collective that is challenging the defunct institutions of democracy and putting a better version of democracy into practice.