Trump's Lump of Coal

The trade deficit is the world’s Christmas gift to the U.S.; Trump’s tariffs substitute a lump of coal.

Part 1 of this series on deindustrialization in New Hampshire used a case study of Kingsbury Machine Tool to explain why the U.S. machine-tool sector fell from dominating the globe to ruin in five short years, from 1979 to 1984. By 1979, global industry had recovered from World War II, and the relative productivity of U.S. workers was declining—that is, U.S. workers produced more efficiently than they had in earlier years, yet the Germans and particularly the Japanese were dramatically more efficient than a decade earlier. To keep U.S. products at the same prices as their international competitors, the U.S. exchange rate should have weakened relative to the value of the Deutsche Mark and the Yen. Nixon started to let that happen in 1973. But Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker, appointed by President Carter, pushed the dollar’s value back up from 1979 to 1982. This policy opened up a 30% price difference between U.S. and Japanese machine tools by 1984. Machine tool firms filled with skilled machinists started collapsing up and down the Connecticut River Valley, nearly leading to violence between owners and workers on the shop floor. Yet this macro explanation leaves a nagging question: Why didn’t a single U.S. machine tool firm make some tool that was so innovative that even a strong dollar could not deter global customers? Had Americans lost their ingenuity?

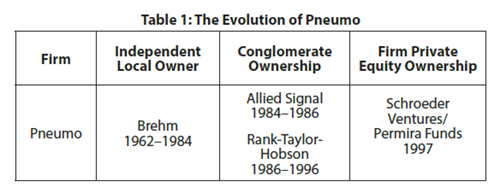

Just such a spectacular invention was developed in Keene, N.H., and it came to market in 1981 and was highly successful. The developer was Don Brehm, the tool was the Diamond Turning Machine (DTM), and the people who made it happen were the staff of Pneumo Precision. The reason we don’t know about it is because the structure of U.S. finance forced Brehm to sell the firm by 1984. He founded precision startups again in 1988 and 2004. Each time, U.S. financial or legal institutions hindered his path. He retired at 72, but ultra-precision DTMs are still manufactured in Keene by two head-to-head competitors: the independent company Moore Nanotechnology, and corporate behemoth Ametek Precitech. Parts I and II of this series considered capital-goods firms that went into decline. In contrast, the story of diamond turning illustrates how small firms independent of the stock market overcome the obstacles that U.S. financial and legal institutions have put in their way all the way up to the present day.

The story of diamond turning begins at a Keene firm connected to the space program in the 1960s, Miniature Precision Bearings (MPB), which later became Timken Superprecision. Part 2 of this series explored how the lure of the rising stock market between 1988 and 2000 led Timken to shut down its local precision engineering laboratory in 2003 (though production still takes place in Keene). That lab was in its heyday in 1956 when 20-year-old Brehm obtained a summer job there between his junior and senior years in the engineering program at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y. That year MPB made the pages of American Machinist and MPB’s owner was interviewed by the New Yorker—heady days. Brehm was a roving quality-control inspector, which meant he could put his hands on the brand-new precision machines on the shop floor, and he came to know a machinist named Dick Robbins who tinkered with them. Upon graduating in 1958, Brehm got a plum job at Pratt & Whitney Aircraft in Hartford, Conn.—only to find himself stuck in a cubicle alongside 60 others. He dreamed of the hands-on work with cutting-edge technology back in Keene and by 1961 had returned to MPB’s precision lab.

There Brehm was tasked with improving the accuracy of measuring the roundness of miniature bearings. The key to the quality of metal parts is the tools used to measure the precision of the machines that make them; designing measuring instruments is known as metrology. The more accurate the metrology, the tighter the tolerances to which miniature bearings could be held, and the more energy efficient the mechanism for which the bearings reduced friction. In 1961, there were miniature bearings behind every dial in a NASA rocket. The premier engineering lab in the United States at the time, the Oak Ridge nuclear program in Tennessee, was using air bearings—a cushion of air between metal parts to reduce friction. “At that time Union Carbide ran the plant at Oakridge,” says Brehm. “And the engineers there had been using air bearings in some machine tool applications. I read about that and thought, ‘Boy, there’s a place for that!’” Brehm used the same cushion of air to develop a roundness gauge to assess the roundness of MPB’s tiny bearings. A tool lubricated with air would be capable of greater precision than the bearings lubricated with grease. Brehm suggested that MPB manufacture the gauge, since he had designed it on the job. But MPB encouraged Brehm to found his own company. The 26-year-old made the rounds, looking for a community banker who would take a chance on his character, given that he had no assets to use as collateral. Dick Dugger at Ashuelot National Bank came through. With $4,000, Brehm opened Pneumo Precision in 1962 in a space rented from MPB, and his first employee was machinist Dick Robbins.

Let’s pause for a moment to consider the pre-1980 institutional structure that acted like yeast to make Brehm’s ingenuity rise into Pneumo. First, there were government-funded laboratories from which engineers freely disseminated their insights into accessible journals. Second, there was an established, privately owned corporation with a lab that did not hoard the patent from its employee’s discovery, but encouraged him to start up on his own. Third, at the community bank, an experienced human being had the authority to grant a startup loan. In this way customer deposits were channeled into local talent. All three structures—government labs, corporations that would forego a patent, and community banks—are hard to find in the landscape of 2018.

The first big break for Pneumo came when Federal Products of Rhode Island picked up the air bearing for its catalog, which had a national and international distribution. “We didn’t have the internet back then,” explains Brehm, so a small company faced challenges in marketing its product. Federal also invited Brehm down to their Rhode Island headquarters to give lectures promoting the use of his gauge to push precision to millionths of an inch. “We were pioneering,” says Brehm.

Everyone who worked there was under 30. Indeed, Brehm’s third employee was right out of high school. That was machinist Dick Arsenault. His wife Carly explained the atmosphere at the time: “Don and Jan [Brehm] were expecting their first baby when we were expecting our first baby. So it was very family oriented.” Arsenault would go on to mentor Keene’s next generation of precision machinists. One of those men was Len Chaloux, who came out of the machining program at Keene State College and later rose into sales at Pneumo. At firms like Pneumo, the sales force explains the technology to customers and brings back technical modifications they request. Machining is largely learned on the job, and it is critical to have a patient and expert teacher. Chaloux had one in Dick Arsenault. Other key players in the early days were Bob Favreau, a skilled craftsman who ground parts for the machine, giving them their edge. Tom Dupell assembled the machines. Bill Mroz was the electrical engineer who stayed after hours to design and install electrical equipment when Pneumo moved into its own building.

Pneumo’s second break came in the 1970s when the Department of Defense invited Brehm to attend its elite engineering seminars at Oak Ridge and Lawrence Livermore National Labs. In an alliance with Moore Tool in Bridgeport, Conn., the DoD had designed tools that used diamond tips for precision on soft surfaces such as uranium. Diamond turning made the hemispherical half shells from enriched uranium that implode to make an atom bomb explode. The half shells had to be very precise so they would implode evenly. Only the government had pockets deep enough to finance this research when it was not yet clear that the technology would work. When the precision machines indeed proved usable, DoD engineers were tasked with passing the innovations on to commercial users, which was the purpose of the seminars to which Brehm found himself invited.

By 1976 Brehm had indeed designed a breakthrough DTM, the MSG 325, with three innovative components. The first was a computer control system for adjusting the machine in response to laser feedback. Note that this computerized machine tool was designed in 1976, the same year that Apple Computer was founded on the other side of the country. “If we had known about Apple, we certainly would have used their computer!” exclaimed Brehm. The second was an air bearing spindle for the diamond-tipped drill that rotates smoothly on a cushion of air, increasing the precision of the tool. Thirdly, the DTM included lasers to control the positioning of the spinning piece of metal relative to the tool. Light beams would detect how the diamond tool and the metal part were coming together, providing feedback to the computer for instantaneous adjustment. Finally, the MSG 325 had a base of Vermont granite to stabilize it. Pneumo’s MSG 325 was the breakthrough machine Americans wish had been developed in time to compete with the Japanese. It actually was.

The trick was to get the financing to bring the machine to market. Unbeknownst to the staff at Pneumo, the global economy was undergoing a sea change by 1976. In 1973, the dollar was decoupled from gold, and exchange rates that had been fixed for decades became unpredictable. Flexible exchange rates opened up a new way to make money, which speculators like George Soros used to their advantage. From 1945 to 1973, if a wealthy individual wanted to make his wealth increase, he either put the money in a bank or the sleepy stock market for a low but steady return, or he took a risk and invested in the more profitable production process by starting a company. These narrow options were no accident. At Bretton Woods, N.H. in 1944, the world’s finance ministers sought to stabilize the international monetary system by shutting down speculation in exchange rates and other instruments in order to channel wealth into job-creation. Consensus opinion in 1944 was that the best way to prevent future wars was to ensure that those with money had to create jobs to make a profit. When the dollar went off gold in 1973, Pandora’s Box was opened, and speculative ways to make money once again competed with production opportunities for dollars. Once exchange rates moved, so did the international prices of commodities (such as oil), so between commodities-futures trading and exchange-rate speculation, there were plenty of new ways to make a lot of money that did not involve industry—a lot of money, and fast.

Community banker Dick Dugger guided Brehm into these turbulent waters by introducing him to colleagues at the larger First National Bank of Boston. That regional bank introduced Brehm to a group of venture capitalists who were willing to bet $350,000 on his computerized precision machine. Venture capital took off after 1973—because the one place where people with knowledge of industry could find returns as high (and risky) as those available in currency markets or commodity futures was in bets placed on the designs of an inventive engineer. The trick was to place the bet when the ideas were still on paper, so that when the breakthrough product came to market, the returns would be spectacular.

There was one catch: Venture capitalists want their money back within five years. So it’s a good thing that by 1981, Brehm and his talented team at Pneumo had succeeded in putting the MSG 325 on the market. The computerized precision machine could manufacture lenses of irregular dimensions known as “aspheres.” That innovation made contacts for astigmatism possible, and in industrial applications one aspheric lens could replace the multiple lenses used in conjunction previously in order to direct light in unusual ways.

Moore Special Tool in Bridgeport, Conn. was Pneumo’s competition. By the 1950s, Moore had invented a remarkably precise lead screw to move the slides that controlled the location of the spinning metal part relative to the diamond tool. As the leader in precision technology, Moore was the DoD’s partner in designing DTMs at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in the 1960s and 1970s. Yet Pneumo eclipsed Moore by the early eighties and came to dominate the market. This was because Pneumo used laser beams and computer controls for improved accuracy.

The venture capital backers of Pneumo converted their financing into shares in the company. These were private shares, which cannot be traded on the stock market. Private shares do not increase in value unless they are sold, which happens rarely. To make shares of Pneumo increase in value more rapidly, at least a portion of Pneumo’s shares had to be listed on the public stock market. That portion would change hands regularly, so that every success of the firm would result in an increased value of all the shares. Venture capitalists who wanted to cash out could then sell their shares on the stock exchange. Brehm hired a Wall Street firm to organize an initial public offering of Pneumo stock. The Wall Street gurus reported back that Pneumo was not a good candidate for listing on the stock exchange.

By refusing to list Pneumo, U.S. financial institutions failed the U.S. machine tool sector. Apple Computer, founded the same year as Pneumo, also received venture capital financing. Apple was able to successfully list on the U.S. stock market in 1980, raising millions with which to repay its backers and to expand with its founder at the helm. Why couldn’t Pneumo do the same? The problem was that hundreds of old-style machine tool firms were either going bankrupt or laying off workers between 1979 and 1984. Wall Street assumed that Pneumo shares were issued from a dying sector, not from the high tech world of laser beams and computers, and wanted nothing to do with them.

Let’s go back to that shudder running through the economy in the 1970s. When Fed Chair Volcker raised interest rates sky-high in 1979, the high rates acted as a magnet pulling wealth from all over the world into U.S. banks. Awash with foreign cash, banks began to offer credit cards to people of modest means. Wall Street would come to love the products that could fill a debt-financed consumer boom, rather than those that helped industry raise its productivity. Apple’s product was classified a consumer good, unlike Pneumo’s.

Brehm did not want to sell Pneumo, which was a great community of people. But the venture capitalists wanted their money back. Furthermore, Brehm had personally mortgaged his home to finance the firm, and as he approached 50, he wanted to get out from under all that debt. Without the option of selling shares in the firm to the public, he had to sell the business. Brehm sold Pneumo in 1984 to Allied Signal, which had recently also purchased MPB.

The post-1973 institutions of finance fund new ideas, but these institutions also push for quick sale of the firm once the product reaches market. This leads to constant change in the ownership of private industry, which fractures the human relationships essential to collaboration. Every sale always raises the same question: Who really owns the firm? One person with an inventive mind, or the crew that made it all come together? Furthermore, the push to sell the startup at the first signs of success promotes wealth inequality. The struggles of the founding engineer and staff to keep the firm going in the early days put everyone on the same page. The pressure to sell off startups puts stress on once-collaborative relationships, and the sudden emergence of wealth inequality pushes people farther apart.

Allied Signal’s terms prevented Brehm from creating a second precision machine firm after the sale, when he would finally have the funds to do so. He had to sign a four-year non-compete agreement. Not one to sit around and do nothing, Brehm started a woodworking business, which did not compete with Pneumo. The legal and financial institutions of the eighties prevented a man who would go on to win the lifetime achievement award from the American Society for Precision Engineering from developing machine tools between 1984 and 1988, precisely when the U.S. machine tool sector was desperately struggling to adapt to major technological change.

Len Chaloux, Tom Dupell, and others from the original crew continued to staff Pneumo after it moved to Allied Signal. The conglomerate owned multiple firms that made unrelated products. The conglomerate business model takes the profits from successful firms and uses them to prop up returns at the less successful. Thus profits from Pneumo would not necessarily be reinvested into the firm, but might be diverted to prop up other entities. Allied Signal’s lackadaisical management of Pneumo benefitted from the fact that Brehm could not found a competitor company.

Chaloux and Dupell were relieved when the conglomerate sold Pneumo to Rank-Taylor-Hobson a few years later. Taylor-Hobson (TH) is a metrology firm in England whose origins lie with cinematic photography. TH was later bought out by the conglomerate Rank. TH engineers appreciated Penumo, and even today there is a connection between Keene and Leicester, where Taylor-Hobson makes its metrology. Chaloux went to England to train the TH people in Pneumo’s technology. Unfortunately for Keene’s precision technology community, TH moved production of Pneumo’s DTMs to England in 1994. By 1997, Chaloux would be head of remaining operations for what was now called Rank Pneumo in the United States.

In 1996, Rank sold Pneumo’s parent, TH, to Schroeder, a British venture-capital firm that would soon become a private-equity firm called Permira Funds. Where venture capitalists make their money by helping a firm bring its idea to market, private equity uses other people’s money (hedge funds, pension funds, or sovereign-wealth funds) to purchase companies that are already producing a product. The PE firm attempts to increase the asset value of the company in a very short time. One way to do so is to borrow money and expand in short order; the debt accrues to the company, not to the PE firm. A second way is by cutting costs and raising selling prices to customers, which generates profits in the short run, thereby increasing the valuation of the firm. In the long run, PE ownership often demoralizes staff and leads to discontented customers. So PE firms sometimes buy out the competitors of their target acquisitions in order to prevent staff and customers from jumping ship.

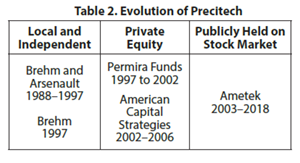

Just such a competitor had emerged in Keene. Back in 1988 Federal Products of Rhode Island, which gave Pneumo its first big break, called Brehm to ask if he could make air bearing spindles for a lower price than what Rank Pneumo was offering. Around the same time, Dick Arsenault, the machining supervisor from the original Pneumo, let Brehm know that he’d run the machine shop if Brehm wanted to open a new firm. By 1988, the non-compete was up, so Brehm and Arsenault opened a new business called Precitech.

The old team from Brehm’s Pneumo was now split in two. Chaloux and Dupell were at Pneumo. They wanted Pneumo to make it past the rough times of management by a European private-equity firm. But after TH relocated production to the U.K., talented staff started jumping ship for the new Precitech, and customers migrated, too. Precitech grew from a handful of people to 100 employees in under ten years. But that had its drawbacks. Dick Arsenault found that it wasn’t much fun working at a large firm and cashed out his ownership share in 1997. Chaloux wondered how he could keep Pneumo vibrant, despite a dubious corporate parent, the transfer of production to England, and migration of staff to Precitech. Chaloux came up with two options: Permira could buy out Precitech, or Pneumo could reach out to Moore Tool down in Bridgeport—those pioneers of DTM whose lead screw technology had been superseded by Brehm’s MSG 325 in 1981. An alliance with Pneumo under Chaloux’s management was an opportunity for Moore Tool to get back into diamond turning. That alliance is where Chaloux thought Pneumo was heading.

But Permira Funds went for option one: They called Brehm from England and threatened to use their deep pockets (of other people’s money) to put Brehm out of business unless he sold. He considered his age—over 60 in 1997. None of his children wanted to take on the business. So he sold the company to Permira. Brehm’s sale of Precitech came as a shock to Keene. A howl of pain and resentment shot through Precitech’s staff. Of the two head-to-head competitors in Keene, it seemed that Chaloux’s Pneumo had come out on top. But in another dramatic turn of events for Keene’s precision community, the British private-equity firm let Chaloux go the day after merging with Precitech, and then changed the combined firm’s name to Precitech. Pneumo was no more.

Len Chaloux was not a man to take a mid-career layoff as the end of his story. He reached out to Newman Marsilius III, who owned Moore Tool, and received an offer of $2 million to finance a new firm. Marsilius suggested locating it in Bridgeport, but Chaloux held out for Swanzey, one town over from Keene.

Marsilius had inherited his family’s business, Producto, around 1985, when machine tool firms were crashing due to exchange rate misalignment. Producto made the castings that stabilized Bridgeport milling machines. By 1985, Bridgeport was in steep decline. Even today Bridgeport has the lowest housing prices in Connecticut—a far cry from the million dollar mansions of Greenwich. There is a vibrant community of Portuguese immigrants holding the town together, some still working at Producto.

In 1994, Marsilius diversified by purchasing Bridgeport-based Moore Special Tool. The sale resulted from an unusual situation: A troubled Moore went up for sale in 1989 to a Japanese firm, but because Moore had partnered with DoD nuclear labs in the fifties and sixties, there was a public outcry that the United States was selling its secrets to the Japanese. The sale was called off, and instead the Marsilius family purchased the firm, possibly at an attractive price. Marsilius then formed the PMT Group (P for Producto and MT for Moore Tool). The firm manufactures precision jig grinders and castings at its facility in Bridgeport, hiring young machinists right out of the local community college. Moore jig grinders make the flattest surfaces in the world.

After purchasing Moore Special Tool in 1994, Marsilius was disappointed to learn that Moore had been surpassed by Pneumo and no longer dominated diamond turning. In the 1990s, Marsilius ran into Chaloux at a conference. The two discussed possibilities for collaboration between Rank Pneumo and Moore Tool. They flouted private equity and formed another diamond-turning enterprise right under the nose of Precitech.

The Marsilius family put up $2 million to found Moore Nanotech. Compare that with the deep pockets of the competition. In 1997, Permira managed a fund of $40 billion. In 2017, Ametek had assets of $7.8 billion—3,900 times as much as $2 million! Is such a small amount of money as $2 million really all it takes to found a firm on the cutting edge of precision technology? There was a catch: Moore Nanotech purchases some key components. Ametek’s Precitech has a larger facility where they make parts themselves. If that were the only difference, Ametek might make the better machine. But for all its deep pockets, Ametek does not manage Precitech as wisely as Moore.

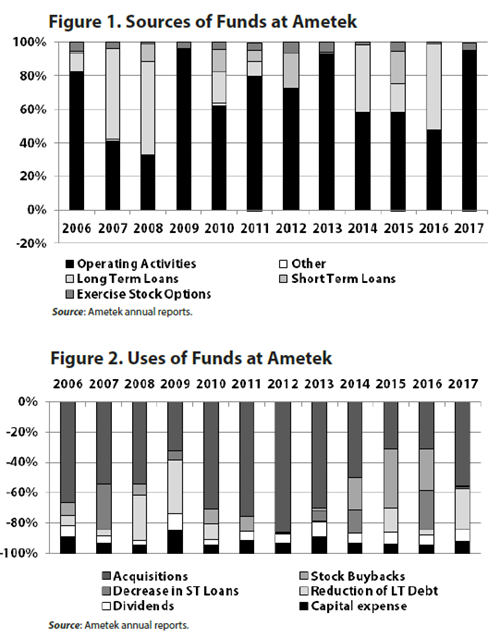

Like most firms listed on the stock market, Ametek uses share price as the metric of success or failure. As Part 2 of this series discussed, share price is far more volatile than the rate of profit. Once share price is the metric, a firm has to mitigate potentially devastating downturns in shareholder value. This can be done by producing multiple products in multiple markets, so that bad news for any one product line in a single country will have minor impact. A constant stream of debt-financed acquisitions achieves diversification of products and markets but breaks the human ties necessary for innovation. Furthermore, local plant managers find it a constant challenge to get the parent company to put money into the existing plants. As Figure 1 shows, Ametek’s funds come largely from existing operations, but that is not where the funds are invested. Figure 2 illustrates that typically less than 10% of the firm’s cash is spent on new capital equipment. It is worth reminding ourselves that acquisitions of profitable firms will make Ametek look large and profitable (it is buying profits), but acquisition does not expand the industrial base as a whole. Instead, acquisition simply transfers ownership of already existing pieces of the industrial base. Acquisitions also exacerbate wealth inequality, since the owner of the firm sold is paid a large sum, while the working people often lose their jobs. Society does not accumulate capital with acquisitions, and social divisions are increased. The shareholder-value business model leads to decreasing growth of U.S. productivity and a demoralized workforce—exactly what the broader United States is experiencing. Figure 2 also illustrates that Ametek uses borrowed money to buy shares of its own stock.

Stock buybacks were illegal prior to 1982, on the grounds that they distort a firm’s share price away from reflecting the firm’s fundamental value. Buyers of Ametek stock are betting that the firm’s existing plants will be adequate collateral for obtaining loans for acquisitions and stock buybacks. If an acquisition fails, or the global macroeconomy affects share price negatively, Ametek could buy shares of its own stock to keep the share price moving up.

Marsilius and Chaloux have operated Moore Nanotechnology differently. Like most small firms, Nanotech relies upon the quality of its product and customer service to sustain and grow the business. Recruiting top engineers from around the world, giving them time to develop machines, and traveling worldwide to market the product technology are the keys to product quality. Recruiting German-trained personnel has proved important because the German government puts funds into supporting innovation in diamond turning, while the once-premier U.S. government labs have suffered cutbacks. Moore Nanotechnology puts several million dollars of engineering (and computer science) time into upgrading new models of their machines prior to bringing them to market. Common wisdom that robots are replacing people is too hasty: A firm that succeeds on the basis of its reputation for quality at the cutting edge (as small independents do) finds that investment into human talent is the top priority. Why do Ametek and Moore Nanotech behave so differently? Ametek is seeking capital gains on the stock market. Moore Nanotechnology is seeking a flow of profits from sales of product. Moore Nanotech isn’t listed on the stock market, so the firm focuses on product quality and customer service. Twenty years after Brehm sold the firm, Ametek’s Precitech may still produce a quality machine, yet it seems that the plant must gradually be losing its preeminent status (somewhat like Timken, as discussed in Part 2 of this series). Under the shareholder-value model, slow decline after acquisition has undermined the quality of production in towns all over so-called “rural America.”

Given the benefits for humans and technology from the business model that Moore Nanotechnology uses, one hopes that U.S. institutions would reward management for adhering to it. Nothing could be further from the truth. For example, the corporate tax rate in 2017 was 35%, yet Ametek paid only 17% of its income in taxes. Moore Nanotech must have been paying closer to the legitimate rate, because an irate Chaloux called his congressperson to complain. The congressperson simply suggested that he hire a lobbyist, too. After 20 years in business, Moore Nanotech currently employs 70 people. With only $2 million in startup money, you do not waste money on lobbyists. Ametek owns 100 plants, employing 12,000 people, of which Precitech is only one. Such a firm can hire lobbyists and tax-evasion specialists. When the Great Recession hit in 2008, Ametek laid off 1,600 people. A heavy debt-load magnifies losses in a downturn. Moore Nanotechnology, by comparison, expanded into a new high-tech facility in 2009. More challenging was 2001. Marsilius was carrying a high debt-load from the late nineties, as were most businesspeople. The community bank he relied upon in Bridgeport got into trouble and called in the loan. He scrambled to find another lender, finding himself forced to rely upon a Wall Street bank that extracted high fees. Since then, he has shunned debt—quite the opposite of Ametek, which borrowed heavily to finance stock buybacks from 2014 to 2016. If small independent firms are the only ones who can resist the lure of stock market gains—and choose to cut their profits in tough years—to invest in innovation and quality jobs, then we should take better care of our community banks.

The Startup That Didn’t Make It Four years after he sold Precitech, Brehm partnered with Patrick Hurst, a brilliant engineer at Moore Nanotech, to found one more innovative machine- tool firm. The firm, Accura Technics, almost made it. But the private equity owner (American Capital Strategies, or ACAS) of Brehm’s own former startup (Precitech) sapped the energy out of Accura Technics by harassing it through the legal system.

When Brehm and Hurst opened Accura Technics, ACAS Precitech accused them of breaking a non-compete. The argument was that Brehm and Hurst were making precision machines that competed with Precitech machines. However, Precitech machines were precise up to one nanometer (billionth of a meter), while Accura Technics’ machines were precise up to only one micron (millionth of a meter). On those grounds alone, Brehm and Hurst argued that the two machines could not possibly compete. Accura Technics was making a diamond- grinding machine destined for use in auto plants and other conventional industrial operations, rather than the ultra-precision optics customers that ACAS Precitech served. ACAS also charged that an employee Brehm hired away from Precitech had taken a client list with him. On the face of it, it is unbelievable that a court of law would believe that Brehm needed the client list for ultra-precision machining, given that he had owned Precitech himself for ten years. Furthermore, the client list for machines accurate to the nanometer was not going to be the same as the list for machines accurate to only a micron. Brehm had never hired a patent attorney before, and the lawyer he got did not understand the subtleties of his industry. The judge himself says he simply found the lawyers hired by ACAS (a firm worth $11.5 billion) more compelling.

As so often happens in the financialized economy, ACAS Precitech competed not by innovating, but by preventing another firm from innovating. Non-compete agreements are similar to patents—ostensibly designed to protect innovation, changes to the legal code now permit the unscrupulous to tie down staff to bad management and prevent others from adopting new technology. The lawsuit cost Brehm and Hurst $150,000, but more to the point, it sucked the life out of their startup. UNC Chapel Hill snapped Hurst up for their precision technology think tank. Keene’s industrial base lost the mind most likely to spearhead innovation in the coming years.

The second setback for Accura Technics came from MPB, now known as Timken Superprecision. (see “Rising Asset Bubbles Distort the Industrial Base,” March/April 2018). In 2003 Keene-based Timken management planned to purchase Accura Technics’ grinding machines to upgrade their plant. “They sure need this new machine,” Brehm remembers thinking after seeing how the plant’s equipment had aged on a walkthrough. Yet Timken suddenly canceled the order. Timken’s annual reports illustrate that headquarters in Ohio decided in 2003 to use all available cash and a lot of debt besides to purchase the competition, Torrington Bearings. Over the next few years, Timken closed plants in Torrington, Conn., setting off more decline. Suppressing competition was an increasingly common tactic of the publicly held corporation in the 21st century, given that the focus on shareholder value in the 1990s had persuaded many firms to eschew investment in new equipment in favor of acquisitions. It may be that failure to invest for two decades made staying ahead of the competition the old fashioned way too challenging, while the larger size of firms that had constantly acquired made wielding market power more appealing.

The downturn in 2009 hit the startup hard. After the previous two blows, Accura Technics was in no position for a third. One machine tool distributor expected a 25% fall off in sales in 2009, but instead faced a 65% drop. By 2009, Brehm had carried his startup for 18 months with no sales. He decided that the stars were not aligned for Accura Technics and shut it down. In 1962, as a 26-year-old with no funds or management experience or national reputation, Brehm had founded a successful company that produced possibly the first computer-controlled ultra- precision machine tool in the United States. When forced to sell in 1984 and again in 1997, he may have taken a different lesson: You’d better have some money in the bank before you start a firm. In 2004, as a seasoned entrepreneur with cash in the bank backing an outstanding young engineer, he found that the obstacles to success were far greater than anything he had previously experienced. These obstacles are another clue as to why the United States lost one-third of its manufacturing jobs between 2001 and 2009.

Readers of Part 1 of this series will remember that Bryant Grinding had employed hundreds of people in Springfield, Vt. (half an hour away from Keene) until around 1990. It is heart-wrenching to think that a computerized successor firm nearly came into existence in Keene in 2004, only to be put out of business not by low-wage labor overseas, but rather by the U.S. legal system and a private equity firm.

Firms owned by private equity or by management that have the stock market in mind want to minimize investment into fixed costs—i.e., capital accumulation—in order to use cash to manage the share price and reduce downside risks. Employee morale, product quality, and customer satisfaction erode over time. How do firms that invest less than 10% of their funds into their existing plants manage to stay in business? Non-compete agreements that prevent employees from taking their skills elsewhere, aggressive patent enforcement that prevents the emergence of competitors, threats against independent owners coupled with hefty offers to buy them out—all of these are tools that firms that are managed for shareholder value make use of to stay in business even though product quality and service are not the center of attention.

Firms that remain independent of both private equity and the stock market retain a focus on product quality and continue to invest in skilled people. Worker-owned independents (such as Hypertherm, a firm based in Hanover, N.H., that makes metal-cutting machines) do exist, but most of the firms that have felt secure enough to turn down the cash-rich offers that mega-firms dangle are multi-generational family-managed firms. Brehm did not have a child who wished to run Precitech when he sold it in 1997. Marsilius’ father ran Producto before him, and the fact that he has a son managing the PMT Group gives him a reason to keep it going. People who take on the task of maintaining high-quality precision independents face constant obstacles—but the history of diamond turning in Keene has illustrated that it is possible for precision engineers, computer scientists, machinists, salesman, and administrative staff to produce high-quality, export-competitive products. My students were amazed to find that the DTMs produced by Precitech and Moore Nanotech are used to make the molds for the touchscreens on their computers and the lenses on their cell phone cameras.

What can we do to make independents grow? Community banks provide long-term financing at reasonable interest rates. Working people should have the option to invest pensions in small independent firms though they are not listed on the stock market—a fix that current institutions do not permit. Government labs in the military supply line can disseminate technological breakthroughs and are preferable to private firms that are in the defense sector purely for profit. Our legal system requires reform so that patents and non-competes spur innovation rather than suppressing it. California refuses to enforce non-competes; the rest of the United States should follow the path of the state that leads in innovation. Finally, it is hard for small businesses to resist the quantity of cash that behemoths can offer. Independent manufacturers haven’t gotten much respect for a long time. They get lumped in with giant corporate behemoths, but they are quite distinct entities. There are times when interests of workers and independent owners are different, but 2018 is not one of them. It’s time to pull together and try to protect what we have left, some of which is very good indeed.