Where the Climate Buck Stops

Climate superfunds are a sensible way to put some of the costs back where they belong, but we’ll get them only if the public demands them.

One winter morning in Los Angeles, a group of health care activists set up a street-corner clinic for day laborers. One of the day laborers who lined up for medical tests was Omar Sierra. He got to the head of the line and then took his seat at the testing station. A nurse tied off his arm and inserted the needle to draw blood, when all of a sudden Migra agents came running from across the street. Everybody panicked and ran. Omar tore off the tourniquet, ripped out the needle, and ran as well. He was pretty lucky that day, because he escaped. But a lot of his friends didn't. So when he got home, disturbed about what had happened, he decided to write a song about it, which for a while actually became the anthem of the National Day Laborers Organizing Network.

I'm going to sing you a story friends

That will make you cry

How one day in front of K-Mart

The Migra came down on us

Sent by the sheriff

Of this very same place ...

We don't understand why

We don't know the reason

Why there is so much

Discrimination against us

In the end we'll wind up all the same in the grave ...

With this verse I leave you

I'm tired of singing

Hoping the Migra

Won't come after us again

Because in the end we all have to work.

Omar Sierra tells us the truth: We all have to work, at least if you're part of the working class. But today's reality is also that working has become a crime for millions of people. A few years ago, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents went to the Agriprocessors meat-packing plant in Postville, Iowa, and sent 388 young people from Guatemala to prison for six months for using bad Social Security numbers (see David Bacon, "Railroading Immigrants," The Nation, October 2008 and Peter Rachleff, "Immigrant Rights Are Labor Rights: Postville and the Lessons of the Hormel Strike," Dollars & Sense, September/October 2008). Those folks were deported immediately afterwards. One of them--we know this because ICE told us in the affidavits they used to get the paperwork for the raid--was a young man who had been beaten with a meat hook on the line by his supervisor. He was picked up along with all the rest, imprisoned, and deported. His supervisor went on working.

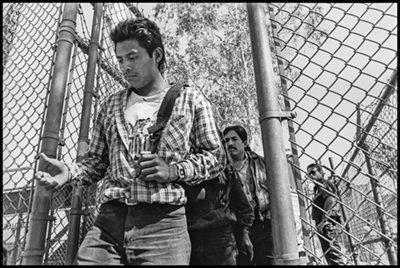

A worker is deported back into Mexico at the border gate in Mexicali, under the baleful stare of a Border Patrol agent. (Credit: All photos (C) David Bacon)

Teresa Mina was a janitor in San Francisco, and she lived in San Francisco for six years. She couldn't see her kids grow up--even though it was for their sake that she came to San Francisco--because she couldn't go home and then pay the thousands of dollars it would have taken for her to re-cross the border and get back to her job. She says, "The woman in the office wouldn't pay me. She said the papers I had when I was hired were no good. I told her I didn't have any other papers. I felt really bad. After so many years of killing myself in that job, I needed to keep it so I could keep sending money home. This law is very unjust. We work day and night to help our children have a better life or just eat," she continues. "My kids won't have what they need now because I can't work."

ICE says on its website that "this kind of enforcement is targeting employers who pay illegal workers substandard wages or force them to endure illegal and intolerable working conditions." But curing intolerable conditions by firing workers certainly doesn't help the workers, and it doesn't change the conditions. Instead, ICE is punishing undocumented workers who earn too much or who demand higher wages or organize unions. Employers in these enforcement actions get rewarded, for cooperating with ICE, with immunity from prosecution, so the only people who get hurt by it are workers.

Michael Chertoff, who was the head of the Migra under Bush, said, "There is an obvious solution to the problem of illegal work, which is you open the front door and you shut the back door." He wants people to come as braceros, as contract workers recruited in Mexico. That's the front door. To make people do that, he would close the back door by picking people up at work or out on the sidewalk or crossing through the desert, because our government says all these things are a crime. That's the message of deporting 400,000 people a year. If you want to come, come as a guest worker, come as a bracero.

E-Verify is the same kind of solution, because it says that if you don't have papers, it is a crime to work. So you stand on a street corner and at truck stops and you get in. And then you work all day in the sun until you're so tired you can hardly make it back to your room. This is a crime. You do it to send money home to your family and the people who depend on you. That's a crime, too.

How many people are breaking the law in these ways? There are 11 million people living in the United States without papers. But this is a global phenomenon. People are going from Morocco to Spain, Turkey to Germany, and Jamaica to the U.K. The World Bank says more than 213 million people worldwide live outside the countries where they were born. Two decades earlier the number was under 156 million. That number increased by 58 million people in 20 years. The number of migrants in the world is going up, and it's going up very quickly. The United States is home these days to about 43 million people born outside its borders, up from 23 million two decades earlier.

If working is a crime, then workers are criminals. And if workers are criminals and working becomes a crime, they will go home. That's one of the justifications for criminalization of migrants. But why don't we see people lined up at the border, paying coyotes thousands of dollars to get smuggled into Mexico? Because there are no jobs for people to go home to.

Mar?a Rosalia Mej?a Marroqu?n, a Guatemalan immigrant, was arrested in an immigration raid at the Agriprocessors meatpacking plant in Postville, Iowa, and was released to care for her child, but had to wear an ankle bracelet to monitor her movements.

The increase in migration to the United States coincided, by no accident, with the period in which neoliberal economic reforms were implemented in those countries that are the main sources of migration to the United States.

In 1994, the year that NAFTA went into effect, there were about 4.5 million people born in Mexico living in the United States. In 2008, that number peaked at about 12.6 million. Of those people, about 5.7 million were able to get some kind of visa. But another 7 million people couldn't, and they came anyway. Fully 9% of the population of Mexico lives here on the north side of the border. People are coming now from the most remote areas of Mexico, where people are still speaking languages that were old when Columbus arrived--Mixteco, Zapoteco, Triqui, Pur?pecha, and others. The largest Salvadoran city in the world is what? San Salvador? No, it's Los Angeles. And remittances going back to El Salvador are 16.6% of Salvadoran GDP.

What produced the migration from Mexico is the same thing that closed factories here. NAFTA, for instance, let huge U.S. companies--Archer Daniels Midland, Cargill, Continental Grain Company--sell corn in Mexico for a price that was lower than what it cost farmers to grow it. Those companies are subsidized by the federal government. The last farm bill had $2 billion in subsidies for U.S. grain producers. Those companies took those subsidies and they sold corn in Mexico at 19% below the U.S. cost of production, according to Jonathan Fox and others who have studied the displacement of people that this has caused. Corn exports to Mexico went from 2 million to 10 million tons from 1992 to 2008.

It's not just corn. The price of pork in Mexico, because of pork exports to Mexico, went down 56%. That didn't mean that it got cheaper in supermarkets. It just meant that those people doing the business made more money. Mexico imported 30,000 tons of pork in 1995, and by 2010 it was 811,000 tons. One company, Smithfield Foods, now controls over 25% of the market for pork meat in Mexico, and as a result, Mexican pig farmers and slaughterhouse workers lost 120,000 jobs, according to the Mexican Pork Producers Association. The systems that helped rural farmers survive by buying corn, tobacco, or coffee at subsidized prices were all ruled illegal, a restraint of trade, under NAFTA. So displacement doesn't just hurt farmers; it hurts workers, too.

In Cananea, a small mining town in Sonora, just south of the U.S. border, miners went on strike in 2008 to stop a multinational corporation from eliminating their jobs and busting their union (see David Bacon, "Mexican Miners Strike for Life," The American Prospect, October 2007 and Anne Fischel and Lin Nelson, "The Assault on Labor in Cananea, Mexico," Dollars & Sense, September/October 2010). When they lost their jobs, the border was there, only 50 miles north. The Mexican government dissolved the Mexican Power and Light Company, which provides electrical service in central Mexico, and fired 44,000 workers. This is a prelude to the privatization of the electrical system in Mexico. Where will those people go? The lack of labor rights, when it gets combined with economic reforms to benefit large corporations, is a source of migration as well.

And then there is environmental pollution. In Veracruz, Smithfield took a beautiful desert valley and turned it into an ecological disaster by building the world's largest pig farm complex. The story of Fausto Lim?n shows the consequences. On some warm nights, Fausto Lim?n's children wake up and vomit from the smell. He puts his wife, two sons, and a daughter into his beat-up pickup, and they drive away from his farm until they can breathe the air without getting sick. Then he parks, and they sleep there for the rest of the night. They all had kidney ailments, all of his family, until they stopped drinking from the well on the farm, because Smithfield had contaminated the whole aquifer under the valley there. Less than half a mile from his house is one of the 80 pig farms built by Smithfield. Each one has over 20,000 hogs. That's where the swine flu started. (See David Bacon, "How U.S. Policies Fueled Mexico's Great Migration," The Nation, January 2012)

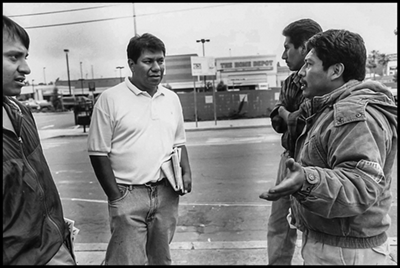

Pablo Alvarado, organizer for the Day Labor Union (and now director of the National Day Labor Organizing Network), talks to a group of day laborers getting work on the corner at Sunset Blvd. in Hollywood.

Victoria Hern?ndez, a teacher in one of the towns in the valley, La Gloria, said that her students would tell her that riding to school on the school bus was like riding in a toilet. She began writing leaflets about it and the ranchers in the valley began protesting about the expansion of these farms. That's when Smithfield had them arrested for defamation in order to stop those protests. Defamation meant telling the truth about what Smithfield was doing.

David Ceja left his home in Veracruz near the Perote Valley and he eventually went to work in a Smithfield plant, the slaughterhouse in Tar Heel, N.C. He says:

The free trade agreement was the cause of our problems. They were just paying as little to farmers as they could. When the prices went up, no one had any money to pay. After the crisis, we couldn't pay for electricity, we just used candles at home. And when you see that your parents don't have any money, that's when you decide to come, to help them. In the ranches where we lived, the coyotes would come by offering to take us north. I was 18 years old when I left in 1999. My parents sold four cows and 10 hectares of land to get the money to get to the border. And then I walked across the river from Tamaulipas to Texas and walked through the mountains for two days and three nights. Some friends told me to go to North Carolina. And in Veracruz we had heard that there was a slaughterhouse there. So when I was hired, I saw people from the area near where I lived. Lots of people from Veracruz worked at Smithfield.

NAFTA and the U.S. and Mexican governments helped big companies get rich by keeping wages low and then giving them subsidies and letting them push farmers into bankruptcy. That's also why it's so hard for families to survive: because they can't farm and because of those low wages. They get laid off to cut costs, their workplaces are privatized, or their unions get busted. On the border, an economy of maquiladoras and low wages was promoted as a way to produce jobs. But in the last recession, in Matamoros or Juarez or Tijuana, hundreds of thousands of people lost their jobs instead. When U.S. consumers stopped buying what those factories were producing, people were laid off. When they were working, it took half a day's wages for a woman to buy a half-gallon of milk for her kids. People live in houses made out of materials cast off from the plants, in homes that often don't have any sewer system, on dirt roads, in terrible conditions. And that's when people are working.

So when people lose those jobs and the border is right there, where are they going to go? We all will do whatever it takes for our families to survive. If it's going north, that's what people do.

The DACA youth, the "dreamers" are the true children of NAFTA--those who, more than anyone, paid the price for the agreement. Their parents brought them with them when they crossed the border without papers, choosing survival over hunger, seeking to keep their families together and give them a future.

Ram?n Torres, head of the strike committee and president of Familias Unidas por la Justicia, a union of indigenous Mexican farm workers in Washington State, talks to strikers at Sakuma Farms about the effort to get the company to sign an agreement. After four years of strikes and the boycott of Driscolls' berries, the union signed its first contract in June.

Today's criminalization programs, the raids and the firings, are very tightly tied to the labor supply schemes, because fear and vulnerability make it harder for workers to organize and for unions to help and represent them. The displacement of people is an unspoken tool of that policy, because it produces workers.

This is an old story in the United States. It was a crime for decades, for instance, for Filipinos to marry women who were not Filipinas, because of anti-miscegenation laws. At the same time, our immigration laws kept women from coming from the Philippines, so for the farm workers of the 1930s and '40s it was a crime to have a family. Many men stayed single their whole lives, moving from labor camp to labor camp, contributing their labor wherever the growers needed it.

The braceros were "legal" because they had visas, the same thing employers say today about contract workers recruited in the H2-A and H2-B visa programs. But let's remember the true history. The braceros lived behind barbed wire in camps. If they went on strike, they were deported. They didn't get all the pay they were owed, and when their contract was over, they had to leave the country.

But the history of this abuse is also a history of resistance. Filipinos fought to stay, and just for the right to have a family. The braceros fought to stay, too. Some people just walked out of those labor camps, and kept on living and working without documents for 20 years, until the immigration amnesty of 1986. They are the grandparents of many, many families living in the United States today.

In 1964, people like Bert Corona, Cesar Ch?vez, Dolores Huerta, and Ernesto Galarza, trade unionists and leaders of the Chicano civil rights movement, fought to get Congress to end the bracero program. The next year Mexicans and Filipinos organized a union and they went out on strike in Coachella and Delano, and created the United Farm Workers of America. But they didn't stop there. In 1965, they went back to Congress and demanded a law that would not make workers into braceros for the growers. They demanded a law that prioritized families, and won the family preference system. Today, once you have a green card, you can get your mother or your father or your children to come and join you in the United States. The civil rights movement won that law.

They've starved that system of the visas it needs to function. Now the waiting line is 20 years long for people to bring family members from Mexico City or Manila. Corporate proposals for reforming immigration laws would pull that family preference system apart. Instead they propose systems in which visas are given based on skills that employers want. These ideas would push us backwards into the bracero era again.

Migration is not an accident. Here in the United States, we have an economic system that depends on migration--and on migrants. If all the migrants went home tomorrow, would there be fruit and vegetables in the supermarkets? Who would be cutting up those pigs in Tar Heel? Who would clean the office buildings? Without the labor of today's migrants, the economic system in this country would stop. But do the companies that are using that labor, whether it's growers or the ones who own office buildings and hotels, pay for the needs of the workers' families in the towns that people are coming from? Who pays for the school in San Miguel Cuevas, a town that sends strawberry workers to the fields of California? Who builds the homes there? Who pays for the doctor? Growers and the employers here pay for nothing. They don't pay taxes in Mexico, and a lot of them don't pay taxes in the United States either.

Workers pay for everything. It's a very cheap system for employers. For employers, migration is a labor supply system, and for them it's not broken at all. In fact, it works very well. In the United States, it's cheap because workers without papers pay taxes and Social Security, but for them there are no unemployment benefits, no disability, no retirement. These are things that people fought for won in the New Deal. But if you don't have papers, the New Deal never happened.

We know that the wages of undocumented people are low and families can hardly live on them, but we also know that there's a big difference in wages between a day laborer and a longshoreman. If employers had to pay the same, people's lives would be a lot better. Before the longshoremen organized a union in the United States, they were like day laborers, hired every morning out on the docks. They were considered bums. You wouldn't want your daughter to marry one. Now they send their kids to the university. The union changed their lives. If employers had to raise the wages of immigrants just to the level of the average worker in this country, it would cost them billions of dollars. It's no wonder there's such fierce opposition when people organize unions or worker centers, or do anything to shake this system up.

But immigrants are fighters. It wasn't long ago when janitors sat down in the streets in Washington and across the country and won their right to a union, in a national campaign--Justice for Janitors. Immigrant workers have gone on strike in factories, in office buildings, laundries, hotels, fields. Some unions in this country are growing, and many of them are those that know that immigrant workers are often willing to fight to make things better. The battles fought by immigrant workers are helping to make our union stronger today.

We had a big change in our labor movement in 1999 in Los Angeles. At the AFL-CIO convention that year unions decided to fight to get rid of the law that makes work a crime, and to protect the rights of all workers to organize. With immigrants under attack today, it's important that unions live up to that promise, especially to oppose the firing of millions of workers, including their own members, because of mandatory E-Verify. Administration proposals to reinstate S-Com and 287(g) agreements, that mandate cooperation between the police and immigration authorities, in the past have led to the deportation of hundreds of thousands of people.

This kind of enforcement has an impact on the ability of people to advocate for social change. At Smithfield Foods, one of the world's biggest packinghouses in North Carolina, two raids and 300 firings scared workers so badly that their union drive stopped. But then Mexicans and African Americans found a way to make common cause, and together they won their union organizing drive (see David Bacon, "Unions Come to Smithfield," The American Prospect, December 2008). They said to each other, in effect, We all need better wages and conditions, and we all have the right to work here and to fight for them.

Immigration raids are used to prevent unity between immigrants and other workers. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents made a huge raid on a factory belonging to Howard Industries in Laurel, Miss., and sent 481 workers to a privately run detention center. This raid occurred right before negotiations with the electrical workers unions, in one of the few unionized plants in Mississippi. Jim Evans, the president of the Mississippi Immigrant Rights Alliance and the AFL-CIO representative in Mississippi, says, "This was an attempt to drive a wedge between immigrants, African Americans, white people, and unions."

African Americans make up about 35% of the population in Mississippi. In ten years, immigrants will make up another 10%. The Mississippi Immigrant Rights Alliance and the Black Caucus in the Mississippi legislature believe they can combine those votes with the state's unions and with progressive white people, and get rid of the power structure that's governed Mississippi since the end of Reconstruction. Chokwe Lumumba, the lawyer for the Republic of New Africa, an Black liberation organization in Detroit, and later for the Mississippi Immigrant Rights Alliance, was elected mayor of Jackson, Miss., so this strategy works. Firings and this workplace enforcement are intended to drive a wedge into the heart of that political coalition to stop any possibility for change.

Last year teachers went on strike all over Mexico trying to defeat a kind of education reform that was invented here in the United States. All around Latin America, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has set up business groups that call for privatizing schools and firing teachers. In Mexico, teachers are upset, not just over their own job losses, but because there is so little alternative to migration for their students, for young people in Mexico.

Oaxaca is one of the states sending the largest number of migrants to the United States today. About three-quarters of the 3.4 million people who live in Oaxaca fit into the Mexican government's category of extreme poverty. The illiteracy rate in Oaxaca is over 20%, almost half of all students don't finish elementary school, 12% of homes don't have electricity, a quarter don't have running water, and 40% of the families living in Oaxaca live in a home that has a dirt floor.

But Oaxaca and Mexico are not so exceptional. In developing countries all over the world, people want an alternative: They want the right to a decent life in the communities where they live. Advocating for the right to stay home means that migration should be a choice, something voluntary, not forced. But advocating for policies to give life to this right usually means defying the government. Teachers and their supporters were shot and killed in Nochixtlan during that strike. The lack of human rights is itself a factor that contributes to migration from Oaxaca and Mexico, because it makes it so difficult for people to organize for change.

There are alternative proposals for changing this system to benefit workers and families instead. The American Friends Service Committee's document, called "A New Path," lays out principles for a humane immigration reform. So do proposals from the Binational Front of Indigenous Organizations and a network called The Dignity Campaign. They all start by asking not what Congress will vote for, but what will solve the problems of working people.

They propose legalization--green cards or permanent residence visas--that would let people live normal lives in families and communities. They advocate eliminating the criminalization of immigrants--no more deportations, no more detention centers, no more using the police as immigration agents, and no E-Verify database to target workers for firings. Instead, they propose a system based equality and rights, and oppose guest worker programs.

Families in Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, or the Philippines have a right to survive as well. Young people have a right to not migrate. And for that, people need jobs and productive farms and good schools and health care. Changing agreements like NAFTA should be part of any immigration reform proposal, and any process for renegotiating the treaty should look at its impact on the roots of migration.

It's not possible to win progressive changes in immigration law without fighting for jobs, education, health care, and justice. These demands unite people, and that unity can stop raids and create a more just society for everybody, immigrant and non-immigrant alike. This is not just a dream of a remote or impossible future. In 1955, change for farm workers seemed impossible too. In the depth of the Cold War, growers had all the power and workers didn't have any. If you were Black and tried to vote in Mississippi, you could be lynched or your home or your church might be bombed. Yet, ten years later, the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act had passed, a new immigration law protected families, the bracero program was over, and a new union for farm workers had just gone out on strike in Delano.

Many of the same members of Congress who voted against these things in 1955 voted for them in 1965. What changed this country was the Civil Rights movement. Today a movement as strong and powerful, willing to fight for what we really need, can win an immigration system that respects human rights. It can stop deportations and provide a system of security for working families on both sides of the border.