[W]hy should the Palatine Boors be suffered to swarm into our settlements, and by herding together establish their languages and manners to the exclusion of ours? Why should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a colony of Aliens, who will shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us instead of our Anglifying them, and will never adopt our language or customs, any more than they can acquire our complexion?

—Benjamin Franklin, “Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind” (1751)

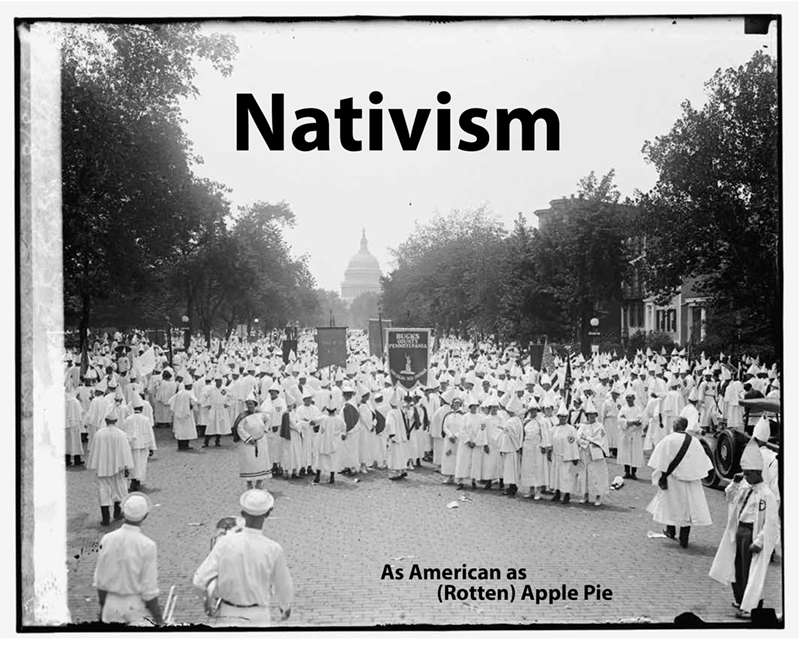

While he was one of the first American nativists, Benjamin Franklin was far from the last. Instead, he inaugurated a tradition that has persisted in American society and politics, occasionally rearing its ugly head to threaten our society. From Franklin, to the Protestant nativists who warned against Irish and German immigrants in the 1850s, to the anti-Chinese crusaders of the 1880s, it was a short step to the Ku Klux Klan movement of the 1920s, which was anti-Catholic and anti-Jewish in addition to being anti-Black. And, of course, to Donald Trump today.

November/December 2016 issue.

Since the United States is largely populated by people who came here from Africa, Asia, and Europe--of course, most who came from Africa were kidnapped and brought involuntarily--it should seem odd for Americans to disparage "aliens." The founding documents of the United States welcomed immigrants. The Declaration of Independence proclaims the equality of all, the Constitution provides that immigrants are to be accorded equal rights with those born here with only minor restrictions, and the first naturalization laws provided for a short and easy path to citizenship open to all without restriction. Unlike other countries, the United States has no official language or religion, and all citizens, regardless of place of birth, are guaranteed all the "privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States" and cannot be deprived of "life, liberty, or property" or "equal protection of the laws" without due process.

Indeed, Americans have often maintained an open and welcoming attitude towards immigrants. Through the 19th century, many states allowed all residents to vote without regard for citizenship, and schools and public services were offered in languages other than English. Native English speakers learned German, Spanish, Yiddish, and other languages so that they could do business with their non-English-speaking neighbors. Even now, in the midst of a new nativist surge, public-opinion polls report that a majority of Americans (in contrast with residents of most European countries) believe ethnic and cultural diversity makes the country better. This view attracts significant support across the political spectrum (ranging from nearly half of self-described "conservatives" to over three-fourths of "liberals").

Against such welcoming attitudes has been a stubborn and resilient nativism which has periodically found political expression.

Waves of Immigration and Waves of Nativism

Sometimes, nativism has been linked with national security scares. Fear of a French invasion in 1798, for example, prompted Congress to pass the so-called Alien and Sedition Acts--including the Naturalization Act, which increased the period of residence required for immigrants to become full citizens from just five years to 14. Another law authorized the president to expel without hearing or judicial recourse any noncitizen deemed "dangerous to the peace and safety" of the United States. And the Alien Enemies Act authorized the president to arrest, imprison, or banish any resident alien hailing from a country against which the United States has declared war.

These anti-immigrant measures were defended by Federalist politicians who warned against inviting "hordes of Wild Irishmen, nor the turbulent and disorderly of all the world, to come here with a basic view to distract our tranquility." The passing of the war scare and the defeat of the Federalists in the elections of 1800 led to repeal of two of the Alien Acts in 1801. After the repeal, political nativism was weakened for the next few decades--possibly as a result of embarrassment at this experience. Widespread nativist politics only returned in the 1850s, after famine and civil war led to a dramatic increase in European immigration. Compared to previous decades, annual immigration to the United States increased four-fold in the 1840s , including an annual influx of over 150,000 fleeing the Irish famine. While each year's immigration equaled barely 1% of the population of the United States, and the Irish were less than half of that, the concentration of Irish immigrants in a few localities had large economic and political effects.

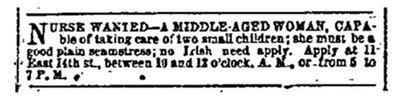

Fears of labor-market competition have also stoked nativist movements. In cities like Boston and New York, Irish immigrants quickly came to dominate the market for common laborers, including construction workers and domestic servants. Often desperate for money and food, the Irish took any work they could find: cleaning stables, unloading ships, digging trenches.

While avoiding the southern states with slave labor and agricultural economies, the new immigrants spread throughout the Northern states. In New England, the Irish would settle in Lynn to work in the shoe factories, or in Lowell and Lawrence to operate looms in the textile mills and build the dams that powered the factories. Around Boston, as throughout the United States, Irish immigrants built the roads and laid the track for the network of railroads that came to tie together the United States after 1850.

Not that their work was appreciated by all of their neighbors.

The flag of the American Party (or "Know Nothings"), c. 1850. Credit: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Native American Party (renamed the "American Party" in 1855 but better known as the "Know Nothings") ran candidates on an anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant platform. At its peak, in the mid-1850s, the Know Nothings dominated the Massachusetts legislature and elected mayors in Philadelphia, Chicago, and other cities. The Know Nothings were more than an electoral vehicle. In 1854, election-related violence led to the deaths of 22 people in Louisville, Ky., and the burning of a Catholic church in Bath, Me., among other incidents.

After 1854, the Know Nothings faded quickly when "Bleeding Kansas" and slavery replaced immigration as the major political issues. For decades after the Civil War, the prominent role that many Irish- and German-born soldiers played in the Union cause may have contributed to the sharp decline of nativism. When nativism returned in the 1880s, its center had moved west to the Pacific coast, and it had a new focus with attacks on Asian immigrants, especially the Chinese.

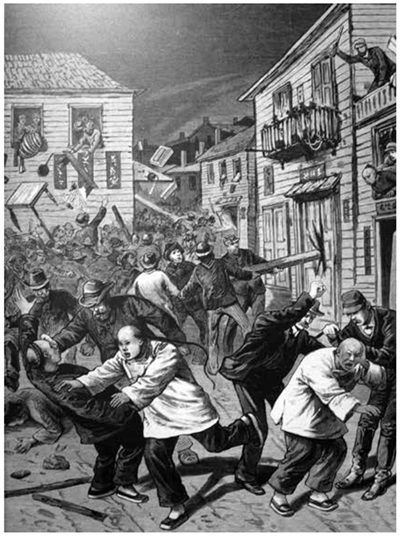

Like the Irish before them, Chinese immigrants took many of the hardest and dirtiest jobs, working in laundries, in construction gangs building railroads, and in mines. Chinese workers dug much of the gold during the California Gold Rush, and many died building the First Transcontinental Railroad. Competition for work and the use of Chinese workers as strike-breakers certainly contributed to the anti-Chinese campaign. Formed in 1876 to "rid the country of Chinese cheap labor," the Workingmen's Party of California was led by an Irish immigrant, Denis Kearney, who liked to end his speeches with the phrase: "Whatever happens, the Chinese must go!"

Nativist movements have been opposed by advocates of equal rights (though not always successfully). While some Republicans and most Democrats joined Kearney in his racism, most Republicans, especially radicals and former abolitionists, defended the Chinese and other immigrants. The great Massachusetts abolitionist Sen. Charles Sumner (R) insisted on equal rights for the Chinese: it is, he said, "the question of the Declaration of Independence and whether we will be true to it. 'All men are created equal' without distinction of color." Sen. Samuel Pomeroy, a Kansas Republican, agreed and pragmatically warned that denying equal rights to the Chinese would threaten the rights of all: "If you deny citizenship to a large class, you have a dangerous element; you have an element that you can enslave; you have an element in the community that you can proscribe."

The Anti-Chinese Riot in Denver on October 31, 1880; Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 1880. Credit: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Such warnings fell on deaf ears after the end of Reconstruction. The return of Democrats to power in the South brought to Congress a large racist block just when anxious northern Republicans feared to push an aggressive equal-rights agenda. A united Democratic Party was joined by enough Republicans to enact racist laws against the Chinese. In 1875, Congress, with a newly elected Democratic majority, enacted the Page Act preventing Chinese women from entering the United States on the assumption that they were prostitutes. And, in 1878, Congress passed a Chinese Exclusion Act. Vetoed by Republican President Rutherford B. Hayes, it was eventually signed into law by Chester A. Arthur in 1882.

As memories of the Civil War and emancipation struggles faded, and migration from southern and eastern Europe surged, nativism spread. In 1894, three Harvard graduates, Charles Warren, Robert DeCourcy Ward, and Prescott Farnsworth Hall, met in Boston to form the Immigration Restriction League (IRL). Arguing that these recently arrived "undesirables" were inherently unable to participate in self-government or to adopt American values, the IRL sought to "arouse public opinion to the necessity of a further exclusion of elements undesirable for citizenship or injurious to our national character."

The IRL quickly attracted a large membership, including many prominent scholars and philanthropists. On its behalf, Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge (R-Mass.) sponsored a literacy bill to prohibit the entry of immigrants unable to read at least 40 words in any language. In 1896, Congress enacted the Lodge proposal only to have it vetoed by Pres. Grover Cleveland as contrary to traditional American policy and values. The failure of immigration restriction left the golden door open to new waves of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe: Jews to work in New York's apparel industry, Slavs for the Pennsylvania coal fields and steel mills, and Italians, Greeks, Poles, and others to build and to operate America's growing industries. Re-introduced repeatedly, the proposed literacy test became law only in 1917, during World War I, when Congress overrode President Woodrow Wilson's third veto.

And once again, fears of foreign "subversives" fueled nativism. The war inaugurated a new period of American nativism, one fed less by fear of economic displacement than by fear of subversion and anger at foreign ideas and involvements. The fear was fed by terrorist incidents. On June 2, 1919, for example, followers of the Italian-born anarchist Luigi Galleani exploded bombs in seven cities, including at the homes of John D. Rockefeller and of U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. A progressive Democrat with a pro-labor record in Congress, Palmer met the bombing campaign with a wave of arrests of radicals and by deporting immigrants and others. Called the "Red Scare," Palmer's attacks targeted immigrants as much as anarchists and communists. The Palmer raids resulted in the arrest of over 10,000 labor activists, radicals, and liberals and the deportations of 556 resident aliens. The warrantless arrests and deportations were widely denounced as "utterly illegal" and led to the establishment of the American Civil Liberties Union. Nearly all the resulting arrests were ultimately voided.

The involvement of immigrant radicals and of immigrant workers in the great strike wave of 1919-20 fed nativist fears. Eastern and Southern Europeans were condemned as incapable of assimilation and incapable of responsible self- government because they were genetically inferior. A broad coalition formed around a program of immigration restriction focused on limiting the admission of immigrants from the "lower races" seen as threats to the nation's gene pool, its democratic institutions, and the American "way of life." Immigration laws enacted in 1921 and 1924 created a national-origins quota system, restricting the absolute number of immigrants and the number from southern and eastern Europe.

Legislation restricting immigration did not end the culture war. Nativists flocked to a revived Ku Klux Klan seeking to limit the rights of African-Americans and of immigrants, especially Catholics and Jews. The rise of the Klan in the 1920s was inspired by one of Hollywood's first full-length epics, D.W. Griffith's 1915 "Birth of a Nation." With its story of how the Klan saved white Americans from African-American rapists and corrupt politicians, the firm brought renewed attention to the Klan. Reborn at a rally at Stone Mountain, Ga., shortly after the film's release, the "second era" Klan soon grew beyond its southern base. By 1924, the KKK had four million members, and professed to control over 24 of the nation's 48 state legislatures. The KKK claimed that it prevented Al Smith, the progressive governor of New York State, from winning the Democratic presidential nomination. While this may be an exaggeration, the Klan may have contributed to the wave of lynchings in the early 1920s.

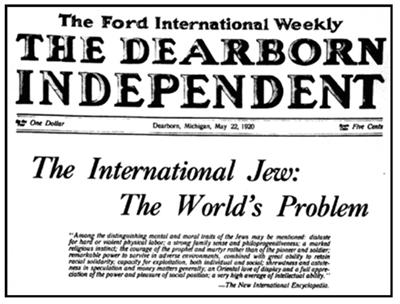

"The International Jew: The World's Problem," in Henry Ford's newspaper The Dearborn Independent, May 22, 1920. Credit: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Beset by corruption and internal dissension, the KKK soon lost most of its new membership. The nativist cause was taken up by others. The industrialist Henry Ford financed the dissemination of the notorious anti-Semitic forgery, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, and for ninety-one consecutive issues beginning May 22, 1920, his weekly newspaper, the Dearborn Independent, published articles describing an international Jewish conspiracy. Broadcasting from his Detroit parish, the Catholic priest Charles Coughlin added economic populism to Ford's anti-Semitism. Coughlin reached a radio audience estimated in the tens of millions with a message that blamed the economic crisis on financiers and communists, especially Jews, who have "murdered more than 20 million Christians" and have stolen "40 billion [dollars] ... of Christian property." Inspired by the success of the German Nazis, he founded a Christian Front to defend the country from communists and Jews and he urged his listeners to "buy Christian."

Coughlin's support for Nazi Germany was his undoing. The association of nativism and racial supremacism with Nazi genocide discredited such ideas. By the 1960s, the United States abandoned the system of national preferences in immigration, opening the country to new waves of immigrants from China, Asia, Africa, and Latin America, as well as the southern and eastern Europeans who had been targeted by the 1921 and 1924 laws.

The (Not So) New Nativism

The repeal of the system of national preferences opened the door to renewed immigration with the number of documented immigrants tripling between the 1960s and 1990s. While the number of immigrants is comparable to past waves, as a share of the much larger population of the 21st century United States, the new immigration wave is much smaller than those of the past. As in the past, however, the new immigration wave has brought migrants from countries previously little represented in the United States. American cities are now filled with immigrants from Africa, Asia, and Latin America, and this is true not only of traditional immigration centers on the East and West Coasts like Boston, New York, and San Francisco, but also big cities in the South and West, like Atlanta and Houston, and small towns throughout the country with motels managed by Indian-Americans, and restaurants and other small businesses run by migrants from throughout the world.

Want ad displaying the qualification "No Irish need apply." New York Herald, July 1863. Credit: Public domain, via IrishCentral.com.

Like the Irish and Germans of the 1840s or the Jews, Italians, and Slavs of 1900, the new immigrants of today are helping to build a new American economy while changing and enriching our culture. And like their predecessors, the new immigrants face racists and nativists. In 1994, California Republicans rode to state-wide victory on their support of Proposition 187, touted as a way to stop undocumented immigration by requiring local police and social services agents to report suspected immigrants. While passed with nearly 60% of the vote, Proposition 187 was never enforced because of challenges in the courts.

Political nativism has found renewed strength after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and, even more, with the economic crisis beginning in 2007. Again, we are seeing the familiar political and economic fears underlying the surge in nativism. While most Americans continue to support allowing immigrants into the United States and allowing those here to become citizens, a very boisterous minority has emerged calling for a restrictive, even punitive, policy like that in Proposition 187. Particularly active in Republican Party politics, nativists have won some signal victories, including the primary defeat of Republican House Majority Leader Eric Cantor. (Cantor, the only Jewish Republican in Congress, supported reforms that would have provided for a path toward citizenship for undocumented migrants.) Cantor's defeat killed immigration reform in the Republican-led Congress, and pointed the way for Donald Trump's successful campaign for the Republican presidential nomination on a nativist program--including a wall on the Mexico border, mass deportation of undocumented immigrants, and "extreme vetting" of immigrants from Islamic countries--not too different from that of the Know Nothings of the 1840s, or the KKK of the 1920s.